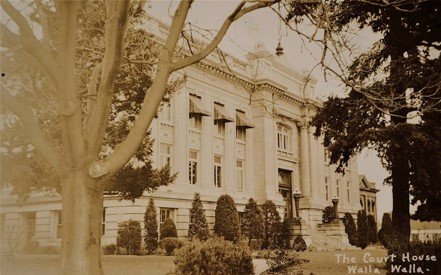

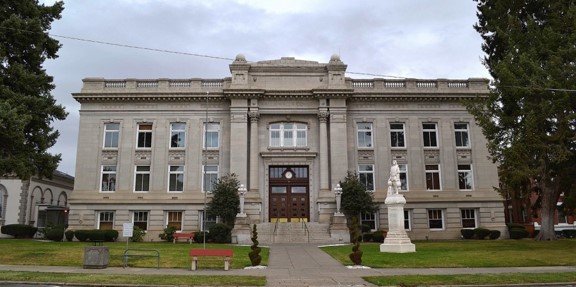

History of 315 West Main Street (Court House Square)

Including County Hall of Records (1891), Old Walla Walla County Jail (1906), and Walla Walla County Court House (1916)

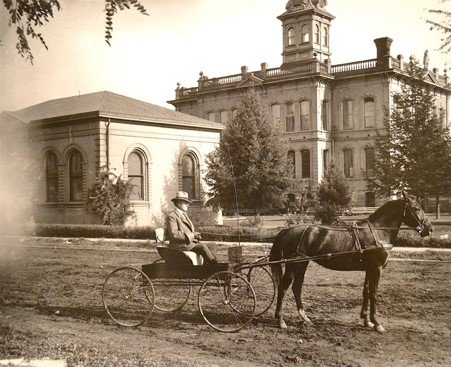

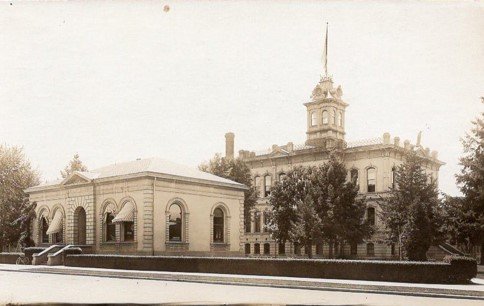

Walla Walla County Court House, center, with Hall of Records, left, and a portion of the former County Jail, far right.

Legal Description

Block number 9 of the City Plat of Walla Walla, as recorded in Volume A of plats at page 1.

Title and Occupant History

Washington Territory was created in 1853. In 1854, the new territorial legislature created Walla Walla County, which stretched from the crest of the Cascade Mountains to the crest of the Rocky Mountains in the present states of Washington, Idaho and Montana. In 1855, Isaac Stevens, governor of Washington Territory, held a council on the banks of Mill Creek at the present site of Walla Walla with representatives of regional Indian tribes to purchase land from them. The Yakamas, Cayuses and Walla Wallas were dissatisfied with the treaties and the intrusion by whites into their lands before the treaties’ ratification, and war followed. Missionaries, former French-Canadian employees of the Hudson Bay Company trading post at Wallula, and soldiers at the military Fort Walla Walla were the primary European occupants of the area prior to 1859, when the treaties were finally ratified and the land was opened for settlement. The transfer of ownership occurred by virtue of a treaty signed on June 9, 1855 in Walla Walla and ratified on March 8, 1859 by President James Buchanan, in which all of the land in the Walla Walla area was acquired from the Cayuse and Walla Walla Indian tribes.

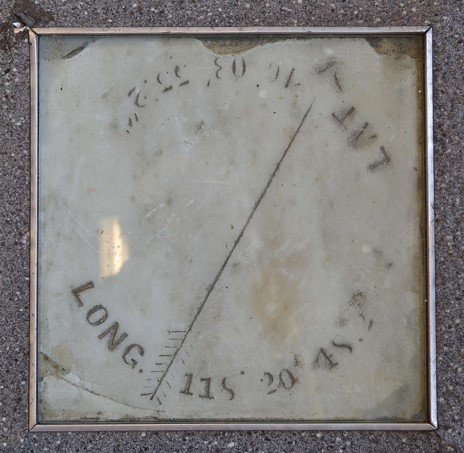

The town of Walla Walla was originally laid out by County Surveyor Hamet Hubbard Case in 1859, prior to its formal incorporation as a city in 1862, as a one-quarter mile square with its eastern side centered on the point where Main Street crossed Mill Creek (at roughly the point where it does now). The original plat was lost, probably in the fire of 1865. Thus, the earliest plat on file is one made by W. W. Johnson, City Surveyor, in July 1865 that claims to have made corrections to Case’s survey. Johnson’s survey was made the official plat of the City of Walla Walla on September 25, 1866, was filed and recorded July 5, 1867.

7/20/1869, United States Government, grantor; City of Walla Walla, County of Walla Walla, W.T., grantee, trustee town site consisting of 80 acres issued by the Vancouver, W.T. District Land Office.

9/17/1870, Warranty Deed, City of Walla Walla in the County of Walla Walla and Territory of Washington, grantor; County of Walla Walla of said Territory, Block 9 as described in the City Plat, better known as Public Square…to have and hold…forever, $100.

The first board of County Commissioners set aside ten acres for public buildings at a meeting on November 7, 1859, but on November 30th reduced the size to one square block, Block 9 of the Original Plat of Walla Walla, bounded by Main and Alder, 5th and 6th Streets.

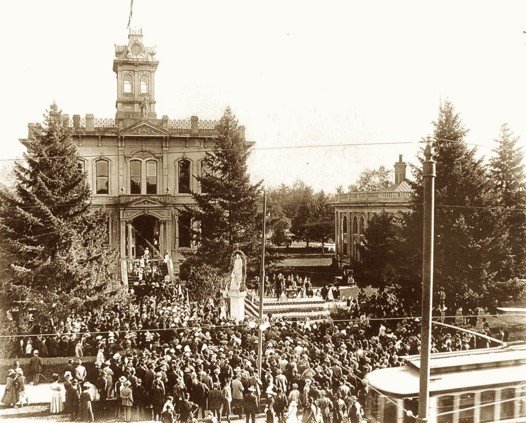

The original plat for the City of Walla Walla as amended by W. W. Johnson consisted of 18 full city blocks, 17 of which were equally divided into ten building lots, plus portions of 12 additional blocks containing varying lesser numbers of building lots. The only complete block that was not divided into building lots was Block 9. Initially this block was known as Public Square and contained no buildings during the years it was owned by the City of Walla Walla, even though it had been set aside as the future location of county government buildings. For an unknown number of years it contained a bandstand on the southwest corner near the intersection of Alder and 6th Streets. Until the time it would contain public buildings it served as a gathering place, a city park of sorts; hence the bandstand. Once the city sold Block 9 to the county in 1870 the name was changed from Public Square to Court House Square. The bandstand remained in place for a time after the former courthouse was built in the middle of the block, but eventually it disappeared. To this day the entire block remains the seat of Walla Walla County government.

Walla Walla County Court House (including prior structures)

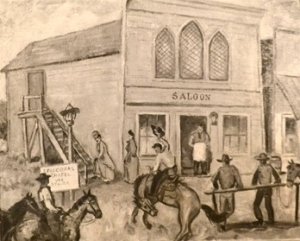

A refined woman glances over her shoulder as she starts up the steps to the Episcopal chapel, perhaps wondering if she and her companion will reach their destination in view of the obstreperous cowpokes watching them. This building later became the first courthouse for Walla Walla County. Dorothy Elliott collection, Whitman Archives.

Prior to acquiring Block 9 in 1870, there was an earlier structure two blocks east that served for some years as a rudimentary courthouse. In Volume 1 of his History of Old Walla Walla County (see References), Prof. W. D. Lyman wrote, “[At] a meeting of March 11, 1867…it was voted to purchase…a building of S. Linkton on the corner of Alder and Third Streets…to be paid for in thirty monthly installments of $100 each. A further expenditure of $500 was made in fitting up the building for the use of the county [as] her first courthouse…and thus Walla Walla was able to hold up a dignified head and note with approval her first courthouse. That the structure was altogether unpretentious and devoid of all architectural beauty it is perhaps needless to say.” What typified this basic building, among many other local structures, before the county purchased it was that it captured all that need be said about the rough and tumble town of Walla Walla in the 1860s; it had a saloon on the main level with an exterior staircase on the left side leading up to the Episcopalians’ then-place of worship! The commissioners voted to expend additional monies to raise the roof of the building five feet and construct a two-story addition 20 by 24 feet (presumably to the rear). Three brick vaults were built to store and preserve county records.

In his 1882 Historic Sketches of Walla Walla County (see References), F. T. Gilbert noted that, “In August [1870] the city council deeded the county commissioners the court-house square on Main street which had originally been set aside for such purposes. The question of building a court-house was being agitated at the time and the commissioners had very properly declined to spend money until the county had a clear title to the land; but after receiving the deed the matter was indefinitely postponed by them.”

Gilbert continued that by 1873, with a clear title to the block, a vote was taken as to whether or not to construct a real courthouse. He noted that although many opposed building such a structure, the majority was in favor – 815 votes for and 603 against. Accordingly, plans for the new building were called for, “…and in February, 1873, those of F. P. Allen [Walla Walla’s most noted architect in the decade before George W. Babcock and Henry Osterman] were adopted for a brick court-house on a stone foundation. The design was for a main building, with an ell that would give ample accommodations to all the county officers, court and jury rooms, and in the basement a jail with twelve cells. There were two stories above the basement, and the whole was surmounted by a dome, making the structure of considerable beauty. Although the county now had a clear title to the court-house square on Main street, there were several parties who desired to enhance the value of their property, and therefore offered to donate land to the county upon which to erect the new building. These offers were considered and rejected, and the court-house square site was selected as the building site. Two weeks later the commissioners saw fit to rescind their former order and accept the offer of four blocks of land between Second and Fourth streets, and one-fourth mile north of Main street, much to the displeasure of the citizens who desired the building erected on the court-house square, where it would not take a Sabbath day’s journey to reach it. The next step by the board was to alter the plans and reduce the size of the building, take off the dome, and prune the structure of all its ornamental features, leaving it the appearance of a huge barn. The last act, and under the circumstances the most judicious one, was a conclusion not to erect the building at all.”

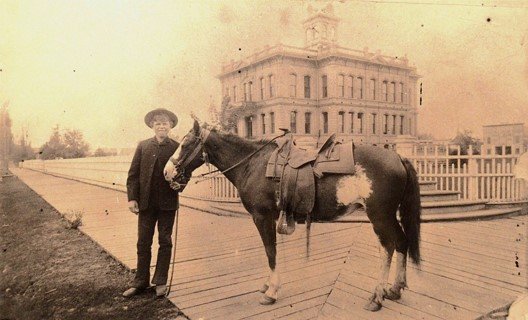

The 1881 Walla Walla County Court House shortly after completion. What was the purpose of the steps that first led visitors through corner gateposts after which they were had to descend to the level of the sidewalk leading to the courthouse entrance? Whitman Archives photo.

For the next few years, the question of a new courthouse remained fallow, but in 1880 the question of levying a tax for the construction of the building was put to a vote of the people and received a near-unanimous endorsement. Absent a wealth of information to document events that followed this vote, it is apparent that the year 1880 saw a rapid move toward approving plans for and constructing a courthouse on Court House Square. Requests for bids were sent out to architects. Architect F. P. Allen revised his earlier plans for the building. On 3/20/1880, the Walla Walla Union reported, “After examining the plans submitted, ordered that the plan for a Court House and jail submitted by Allen & Simpson, be adopted.”

The Washington Standard in Olympia reported on 4/9/1880, “The Walla Walla Union says: The Court House will be 91 feet by 72 feet at its greatest outside measurements; the cornice will be 45 feet above the ground, the whole surmounted by a tower 40 feet above the cornice. The style of architecture is classic, with French ornamentation. The drawings represent a very handsome structure. The material to be used is brick with stone foundation.”

And finally, on 5/20/1880, the Vancouver [W.T.] Independent noted, “The contract for building a court house at Walla Walla has been let to J. R. Addison for $44,540. It will be completed by Nov. 1st.”

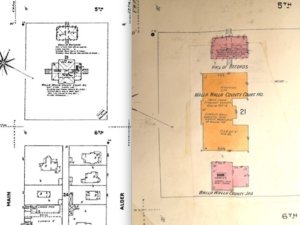

The first edition of the 1905 Sanborn Fire Map, left, shows the 1881 courthouse and the Hall of Records. The bandstand that dates from the time this block was known as Public Square may be seen at the corner of 6th and Alder Streets. The 1905 Sanborn Fire map with 1929 additions, right, shows the current courthouse, the Hall of Records and the former jail. The bandstand is no longer there.

A precise date for completion and/or dedication of the new courthouse could not be located, but it was not completed until 1881. Final cost according to F. T. Gilbert, including furnishings, was about $60,000. The front faced West Main Street, with a centered grand staircase rising to the elevated main entrance, imparting a central massing of the façade that was continued on the other three faces of the building. As were many of F. P. Allen’s buildings, the architecture of the courthouse could be described as picturesque eclecticism, employing a wide variety of ornament. Walla Walla, although still a small and unsophisticated town, was an important seat of territorial government and thus wished to project itself to the country as a political powerhouse, and what better way to accomplish this than to construct a wedding cake seat of government? (Ornamental stucco plaster “frosting” over the bricks allowed for much imitative ornamentation.)

The overall effect was Italianate, as evidenced by the Corinthian columns that supported a small pediment, the exclusive use of broken arch windows on all three levels including the half underground barred jail windows in the basement, and the combining of the two broken arch windows above the entrance under a rounded arch, above which was mounted a statue of Justice on a second, larger pediment. Confusing the Italianate architecture of the main building, the centered tower relied on Second Empire or Mansard architecture with its mansard roof and round arch windows. At the cornice, elaborate wrought iron rails connected the multiplicity of chimneys. Confused, yes, but overall impressive. (Note how closely this building reflects the Columbia County Court House, still in use in Dayton and the oldest operating courthouse in Washington.)

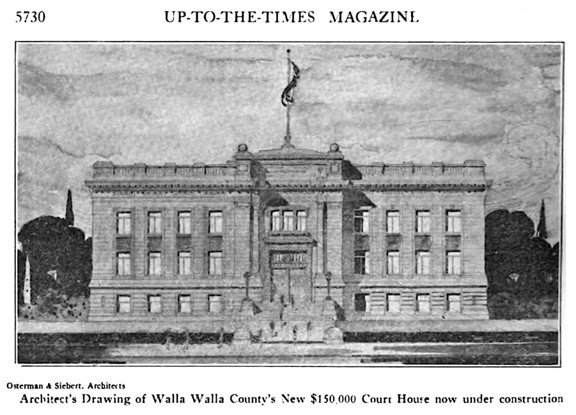

The years during which the old courthouse operated are not well documented. As hard as it is to understand how a building only 31 years old could be declared unsafe, that is what happened in 1912 and it was condemned in 1913. One wonders because the rapidly-growing city had outgrown the 1881 building condemnation would facilitate demolition and replacement that a percentage of citizens might otherwise not support. Prof. Lyman wrote in Vol. 1 of his history of Walla Walla County that, “There were three proposition…from 1910 to 1914. One was to repair the old building, though it had been condemned by experts; another was to make a costly structure at a maximum outlay of $300,000; the third proposal was for a substantial, but plain and modest building of approximately…$150,000. [The] commissioners proceed[ed] with such a plan.” Pending resolution, many county officials moved from the courthouse to the new Elks’ Temple on the northwest corner of 4th and Alder Streets. Having agreed on the less expensive $150,000 new building, the old courthouse was demolished. Up-To-The-Times magazine reported in its February 1915 issue that the old courthouse had already been razed the previous month and construction of the new courthouse was about to begin.

By this time the German émigré Henry Osterman was Walla Walla’s most prominent architect, with offices in the Drumheller Building. He had also taken on the young Victor Siebert as partner, and it was the firm of Osterman & Siebert that was awarded the contract to design the new courthouse for Walla Walla County. Picturesque eclecticism, as represented in the old courthouse and many of F. P. Allen’s designs, had largely faded from popular use by the last quarter of the 19th century; however, because the major metropolitan areas close to the West Coast were so far separated in many ways from the more trend-setting East and Midwest, new architectural trends were more slowly appearing locally. Walla Walla, an important city in a rural location, was still building new houses in Eastlake and Jacobean styles as late as the first decade of the 20th century, styles long-since abandoned in the Midwest and East.

Louis H. Sullivan of Chicago, the “Prophet of Modern Architecture,” had already seen his once-dynamic career peak by the turn of the last century. (The young Frank Lloyd Wright had worked in the office of Adler & Sullivan, and had angered Sullivan by his “moonlighting,” designing projects for clients on his own, allowing him to freely practice and develop his revolutionary ideas about architecture.)

Thus, by the time the County Commissioners had determined to construct a new courthouse there were two distinct schools of thought in American architecture: the modern or progressive school of thought that proceeded along the lines established by Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, Walter Burley Griffin and others; and the Beaux Arts school that adhered to the philosophy that genuine architecture should follow precedent that had been established by the Greeks, the Romans, the French and others – but on a grandiose scale that would project American strength, dignity, wealth and probably dominance. It was this type of architecture that was widely employed for government buildings, banks and other such structures it was thought should display these attributes. Even Walla Walla contains examples of such architecture; two such buildings that exemplify this, both designed by the Seattle firm of Beezer Brothers, are the Banker Boyer National Bank on the corner of 2nd and Main Streets and the former First National Bank, now the main branch of Banner Bank, on the corner of 2nd and Alder Streets.

It follows then that Osterman & Siebert, more eclectic than progressive in their designs, chose Classical Revival for the new courthouse. Indiana limestone was selected for the exterior of the building. The interior spaces are embellished with highly-grained marble from an island off the coast of Alaska, procured via a contract with Walla Walla’s Independent Monument Company. Marble was used for the grand staircase, wainscoting and floors. In an effort to make the building as fireproof as possible, much of the “woodwork” is actually metal with doors and door and window frames and casings displaying faux wood grain. (The Auditor’s vault on the second level still has its metal roll-down window blinds to protect its many books of deeds, plat maps, etc.)

Up-To-The-Times reported in its March 1915 issue that “plans for the new courthouse will be ready for inspection soon by the County Board of Commissioners [for which] Osterman & Siebert are preparing [plans]. It went on to state that the county budget included $62,642.72 for the new courthouse, to be paid for in three years by direct taxation.

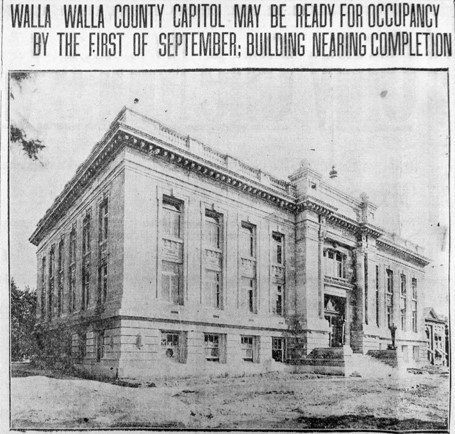

In May 1915, requests for bids for construction were sent out, and those received were opened in May. Local businessmen and some prominent citizens urged that the contract for construction be awarded locally. Commissioners rejected the first set of bids, resulting in a kerfuffle that included 600 citizens who demanded the contract be awarded to the lowest bidder. Eventually the matter was resolved by two of the three commissioners voting to grant the contract to the low bidder, J. B. Sweatt & Company of Spokane, who bid the job at $143,157.

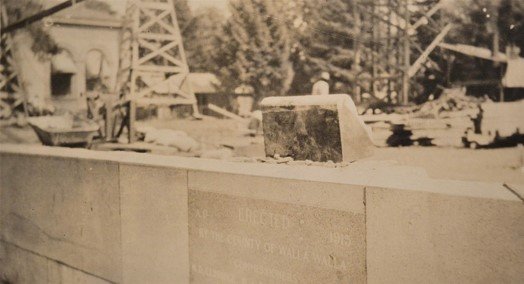

By August 1915 the foundation was nearly completed. G. H. Sutherland Company of Walla Walla, with a bid of $9,964, was awarded the contract to install the heating plant. On the 16th of August a Masonic dedication was held for placement of the cornerstone. A Bible, an American flag, a history and illustrations of the county’s former courthouse buildings, statements of Walla Walla’s banking institutions, and various county newspaper and publications were placed in the vault.

Construction of the new courthouse was slowed by the severe winter of 1915-1916. Whitman Archives photo.

Severe weather over the winter of 1915-16 brought construction progress to a near halt, slowing completion of the new courthouse, which was finished and accepted by the County Commissioners on September 27, 1916.

The 1929 alterations to the 1905 Sanborn Fire Map state that the courthouse is of reinforced concrete construction and was considered to be fireproof (see illustration on Page 5). It appears that the heating plant for the Hall of Justice was updated during construction of the courthouse, as noted on this map, with steam heat being piped from the courthouse to the Hall of Records.

The façade of the new Walla Walla County Court House is almost understated, yet in its simplicity it projects a noble and majestic appearance utilizing restrained ornament. The building is three stories in height with the first floor at ground level. Although this level has walk-in entrances on each side of the building, it is the grand front entrance that was designed for use by the public. The central portico is flanked on each side by massive columns rising two stories in height. Although their Composite capitals are the most complex of the five orders of architecture, their shafts are simple and unfluted. The building lacks a classical pediment; an entablature projecting slightly above the roof contains the following words: Judge Thyself with Sincerity and Thou Wilt Judge Others with Charity. A fairly simple cornice is supported by a multiplicity of corbels, beneath which is a band of egg-and-dart ornament. A classical balustrade tops the cornice.

The small ground-level entrances on each side of the building are rather hidden, and it is by the broad series of granite stairs to a centered double entrance that the public is directed for access to the courthouse. The double set of doors that define the entrance open midpoint between the first and second floors. The view once inside could be described as almost intimidating by the broad, imposing marble staircase that rises to the second floor, continuing halfway to the third floor before separating, turning back and continuing on to the third floor – the floor of Justice where the two courtrooms are located. On either side of the base of the wide marble staircase inside the entry are smaller marble steps leading down to the first level, their somewhat reduced stateliness perhaps reflecting that they lead to offices of more utilitarian types of county government. Also on the lower floor was a jail for juvenile offenders, located in the southeast portion of the building. The juvenile jail is still largely intact, used now for storage by the County Assessor.

The April 1916 issue of Up-To-The-Times contained the following “The court house lawn will be regraded in some parts, walks put on the grade and new flowers planted in some places. With the completion of the court house, with its beautiful architectural design, surrounded by the improved lawn, the court house block will be a source of pride to all citizens.”

The marble staircase ascends from the entry midpoint between the first and second floor to the third floor. Divided smaller stairs on each side of the photo descend one-half floor to the main level.

Although not up to current ADA standards when it opened, a single elevator was installed many years ago, ensuring courthouse access to all via the side doors of the building. Many of the original fixtures remain in place, including numerous ornate glass light shades, and even some restroom fixtures, albeit upgraded. In 2002, tuck-pointing was done to the exterior at a cost of $530,000.

The Walla Walla County Court House is a simple, but excellent, example of early 20th-century Beaux Arts government architecture and should be a valid candidate for placement on the National Register of Historic Places.

Old Walla Walla County Jail (including prior structures)

Although the very early history of a jail in Walla Walla is a bit sketchy, F. T. Gilbert included the following under activities for the year 1860: “…the question of whether a tax for building a courthouse and jail should be levied was submitted to the people, and though…no returns are on file, a negative vote is indicated from the fact that neither were built at that time, prisoners being sent to Fort Vancouver for incarceration.” One wonders whether or not building a holding facility in Walla Walla might, in short time, have paid for itself through saving the expense of transporting offenders all the way to Vancouver.

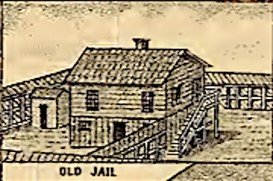

Prof. Lyman wrote in Vol. 1 of his history, “On the 8th of [October 1861] a contract was given Charles Russell to build a county jail at a cost of $3,350. He finished the work in 1862, was paid $6,700 in script for it, and in 1881 re-purchased the same building from the county for $120, and, tearing it down, moved it out to his ranch.”

Seattle had its Katzenjammer Court House; Walla Walla had its Katzenjammer Jail, from which it has been alleged detainees could escape by banging their heads against the wall to make a hole through which to escape. From the border of a larger illustration of the 1881 Walla Walla County Court House featured in West Shore magazine, Portland, undated (probably 1881).

By the mid-1860s it seems apparent that the county had some type of holding facility, as under Annals of 1865 Gilbert reported: “In the spring of 1865 the city council decided to unite with the county in the use of the county jail. Prior to that time they had been paying a rental of forty dollars per month for a building. Although the county jail was very insecure, and had permitted the escape of nearly every prisoner confined on a serious charge, still it was thought that a high fence would render it more safe, and this the city agreed to build for the privilege of using it. It was constructed twelve feet high, enclosing a yard 80 x 84, at an expense of $1,380, and the county added a considerable sum in repairing the jail building. It was at this time that the vigilante organization…was taking charge of affairs, and the authorities were aroused to action.” Continuing about the following year, Gilbert wrote, “Never during its history had the county been supplied with sufficient and proper accommodations. The jail was but a modern skeleton, from which all who were confined on charges serious enough to make escape desirable, were in the habit of escaping, apparently at will. The only way to prevent this was to iron the prisoners, a method so cruel and unjust to men who were simply charged with crimes of which they might be innocent, that it was only resorted to in extreme cases. The grand jury frequently called attention to this condition of affairs, and in 1866 an effort was made to patch up the old structure. The city, for the privilege of using the jail, built a high fence around it, while the county spent a small sum in plugging up the holes made by escaping prisoners, and in fitting up a room over the cells for the jailor to occupy.” Finally, Gilbert wrote for 1866, “At the end of the fiscal year, it was found that the revenue of the city had been $15,358.97 of which $9,135.13 had been derived from licenses. The expenditures fell short of the receipts $93.16. Liquor, hurdy-gurdy saloons and gaming houses furnished the chief revenue from the sale of licenses, and, in fact, about one-half the total cash receipts of the city. On the contrary the expense for police and jail was the largest by far the city had to endure.”

F. P. Allen’s new Walla Walla County Court House, completed in 1881, contained a 12-man jail in the lower level, identifiable in photos by the bars on the windows. With a rapidly increasing population, however, by the turn of the last century commissioners had to face a growing need for a larger county jail. November 4, 1905, the Evening Statesman reported, “Whether or not Walla Walla is to have a new jail building is expected to be settled by the county commissioners at the regular monthly meeting next week. The commissioners will meet Monday morning. The erection of a new jail entirely separate from the court house has been under consideration for several months and progressed so far last month that the commissioners were almost disposed to accept a set of plans submitted by a firm of Spokane architects. If it had not been that the board wished to give such work to Walla Walla contractors, so far as practicable, it is highly probable that the Spokane architects would have landed the job. The board will probably secure plans of different jails in the west and embody their best features into a jail for Walla Walla county when it is decided to build one.”

And on November 10, 1905:

“COMMISSIONERS DECIDE TO ADVERTISE FOR PLANS AND SPECIFICATIONS.

Will be a Two-Story Structure and Must Not Cost Over $30,000 Fully Completed.

The commissioners last night finally decided to erect a new jail building entirely separate from the courthouse and Auditor Honeycutt was instructed to advertise for plans and specifications for a building two stories in height and provided with 10 cells, with room for 10 more, sheriff’s office, jailor’s department, juvenile cells, female cells and culinary department. Architects of Portland, Seattle, Spokane and Walla Walla will be invited to submit plans for such a building, the cost, completed and fully equipped, not to exceed $30,000. Plans will be accepted on December 4 at 2 o’clock.”

The following month on December 6th the Evening Statesman reported the following:

“PLANS FOR NEW JAIL DECIDED UPON.

County Commissioners Make Selection This Afternoon.

Architect Osterman the Lucky One.

A set of plans submitted by Architect Henry Osterman for Walla Walla county’s proposed jail building were accepted by the county commissioners this afternoon. The proposed building will be 51 by 65 feet in size, two stories and a basement in height and must cost not to exceed $35,000. The jail proper will accommodate 28 general prisoners, besides cells being provided for juvenile and female prisoners and insane patients. On the first floor will be located the sheriff’s general and private offices, waiting room, conversation room and conversation cell in connection with jail proper for general prisoners. The female department will also be on the first floor but separate from the general prisoner department. On the second floor will be the insane cells, juvenile department, hospital, kitchen, dining room and sleeping rooms for the jailor [sic]. The jail proper will be absolutely fireproof, having reinforced cement ceilings and floors. There are a few details to be arranged in the matter of material and the board will meet with Architect Osterman this evening to complete the plans. The contract for the building will be let some time next month, bids to be asked for separate on the cell and steel work, construction and building material.”

As if to reinforce the earlier announcement that Henry Osterman had been selected as architect for the proposed new jail, on December 23, 1905 the Evening Statesman wrote that, “After due consideration of all plans submitted for the construction of a new county jail the plans of Henry Osterman are considered the best and accepted subject to some changes.”

On January 4, 1906, the following appeared in the Evening Statesman:

COUNTY JAIL IS ASSURED.

COMMISSIONERS INSTRUCT AUDITOR HONEYCUTT TO ADVERTISE FOR BIDS.

The county commissioners this morning instructed Auditor Honeycutt to advertise for bids for constructing the new county jail building. Three separate bids will be asked for, one for the building proper and the plumbing; one for doing the steel and cell work and one for the heating plant. Bids will be opened at the February meeting of the board and the contract awarded.

Under the headline, NOTICE TO CONTRACTORS, the Evening Statesman on February 6th contained the following:

“Sealed proposals will be received by the Board of County Commissioners of Walla Walla county, Washington, up to 9:30 o’clock A.M. Wednesday, February 7th, 1906, for the erection of a county jail building. Plans and specifications for said building may be seen at the office of Henry Osterman, architect. Walla Walla, Washington. Three separate bids will be received; one for the erection of the building, including plumbing complete; one for the installation of a steam heating plant and one for the installation of steel jail cells, (14 cells with corridors), balconies, window grates and doors. The building to be completed on or before six months from date of contract. Each bid must be accompanied by a certified check for 5 per cent of the amount of the bid as a guarantee that the successful bidder will enter into a contract with the county to complete the work according to the plans and specifications and furnish the required bond. All bids must be marked ‘Bid for jail construction’ and addressed to the undersigned. The Board reserves the right to reject any and all bids. By order of the Board of Commissioners W. J. Honeycutt, County Auditor and Ex-Officio Clerk of the Board of County Commissioners of Walla Walla, Washington.”

Three days later, February 9th, the Evening Statesman reported,

JAIL BUILDING CONTRACT AWARDED

McLEAN & McCALLUM CARRY OFF THE PLUM

McLean & MeCallum. the well-known building firm, was awarded the contract for erecting Walla Walla county’s new jail building late yesterday afternoon. The firm’s bid was $20,400 for a pressed brick and Tenino stone building, erected according to plans and specifications prepared by Architect Henry Osterman. [J. M. McLean was one of Walla Walla’s most prominent contractors. Alexander Taylor of Walla Walla was subcontractor for all brickwork.] The awarding of the cell and steel work for the new jail building will be deferred until next Thursday.

May 11, 1906, it was reported that, “A shipment of steel and cell work for the new county jail has been received from the Pauly Jail company [Pauly Jail Building Company, Noblesville, IN], which was awarded the contract for furnishing the steel part of the new prison now under course of erection. The cell work will be installed by an expert to be sent to Walla Walla from the factory. Before adjourning yesterday evening the county commissioners decided to place $6,000 insurance on the new jail building being erected, and placed $2,000 each with Frankland & Brown, C. G. Church and J. E. Houtchens. of Waitsburg.

As with much new construction, controversy surrounded the cost of the new jail. The Evening Statesman included this humorous article in its August 22, 1906 edition:

COUNTY TAXPAYERS SHOWN WHERE THE GOOD MONEY GOES

“By gum, you had a pretty good jail over thar. Building that new one is what makes our taxes so high.” Thus did Jacob Kibbler, a wealthy Mill Creek farmer, express himself toward the commissioners this morning, when, after glancing over his assessment, he figured out that one reason for the apparent high valuation placed on his broad acres was the fact that the board had spent some $20,000 in building the new county Jail. “Yes, that jail is good enough for anybody.” reiterated Mr. Kibbler, “That’s what I say,” broke in Thos. Kilkerson, another prominent Mill creek farmer, who had accompanied Mr. Kibbler to the commissioners’ room just to look over his assessment. As the two farmers’ remarks seemed to be directed at Commissioner Struthers, the commissioner from the second district saw it was up to him to clear the board’s skirts of the charge of extravagance. “All right, just come over and look at the old jail and see for yourselves,” said Commissioner Struthers and taking the two farmers in tow the trio made a tour of inspection through the old jail. After inspecting the dark cells and dingy, dark corridors and having it explained to them that it was costing the county $3 a day for a night guard besides other incidental expenses, the two farmers were forced to acknowledge that the charge of extravagance had been a trifle premature. The trip through the county bastille proved quite a novelty to the farmers. Mr. Kibbler jokingly wanted to know where they kept the “women folks” and when it was explained to him that it was necessary to keep them locked up in the dark cells while the male prisoners were exercising, he said it was too bad.”

The new jail having been at last completed and accepted by the County Commissioners October 20, 1906, the Evening Statesman reported on November 6th that on November 8th it was, “Ordered that the prisoners be moved to the new county jail without further delay and the sheriff’s office be moved from the Court house to the new jail building. Ordered that the city of Walla Walla be allowed the use of the new jail under direction of the sheriff and that the present private office of the sheriff be used by the city as office room and that the rental be $25.00 per month, including fuel, light, and janitor service for the office room.”

The former Walla Walla County Jail projects a dignified but austere façade, as befits a place of confinement.

The completed jail is a pressed brick structure with Tenino sandstone trim. It is two stories in height, and the main façade projects a central massing, with six steps leading to the center entrance that extends outward slightly from the main structure, above which is a double round arch window flanked on each side by a pair of simple flat brick pilasters. All windows on the second floor are round arch topped with heavy hoods. Each contains a stylized keystone supporting a stringcourse that surrounds the building. The main cornice features a band of dentils underneath, and is topped by a balustrade that surrounds the building, interrupted by the small pediment that caps the entrance projection. The date of construction, 1906, is centered in the pediment. Windows of the first floor are rectangular with sandstone lintels. The fenestration is pleasant, though simple, as befitting a jail, the use of exposed brick probably testifying to the commissioners’ thrift in keeping costs to a minimum.

Numerous interior changes have been made to the old jail since its function as a jail ceased upon completion of a new county jail on the Alder Street side of Court House Square in 1982. Although the cells remain in place, much of the original office space has been reconfigured and is mostly used for storage.

On the main floor are two rows of five cells each, two being four-man cells and three being two-man cells, for a total capacity of 28. None of the cells is furnished with a toilet or basin and crowding would have been a problem from the day the jail was opened. On the second level was the women’s jail, consisting of a single cell with three berths and separate full bath. There are several single cells throughout the building for use as isolation or as a holding cell during the booking process. Originally, as noted in one of the above Statesman articles, there was evidently one cell for “insane” prisoners, and until the new courthouse was constructed in 1916, juveniles were also held in the county jail.

The second floor also included a mess hall and kitchen, and a small apartment for one live-in deputy, the only officer on duty overnight.

The basement contains the original heating plant, no longer functional, a property room for inmates’ personal belongings and a dark room, presumably where booking mug shots were developed.

What is most certainly an urban legend postulates that the cells for the 1906 jail were removed from a ship where they had served as a brig. It is unlikely that a ship’s brig would contain cells for over 30 detainees, and it is likely that a brig for a ship would have to be designed to accommodate the contours of the ship’s hull. If this story has merit it would be more plausible to assume it was for a jail that predated the 1881 County Court House.

The old Walla Walla County Jail building appears to be in an acceptable state of repair on the exterior; the interior, however, is currently a series of chaotic spaces, the cellblocks being unusable and in need of removal were the building to be repurposed for office space. Nonetheless, the building is a pleasant structure and is certainly a contributor to Court House Square were it to be considered for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places.

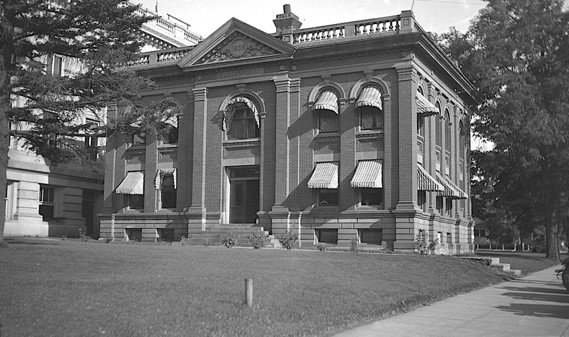

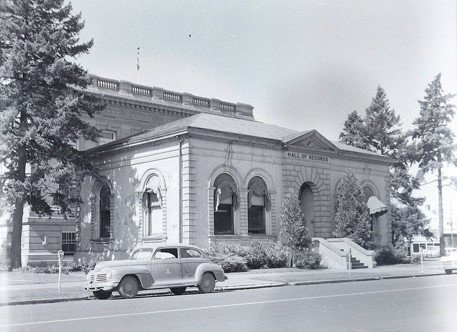

Hall of Records

The Hall of Records, the third of the triptych of historic buildings on Court House Square, seems to be the one with the least documented history. Its name suggests it was built for the primary purpose of records storage, and, indeed, the large round arch windows at one time had metal roll-up blinds as a precaution against fire; the ornamental overhead containers to store the blinds when rolled up are also metal. Offices for the County Commissioners were moved to the Hall of Records at some point, as the Morning Union newspaper reported on 4/6/1909 that the commissioners “met all day in their offices in the Hall of Records for ‘nothing but routine work…the time being taken with the consideration of small matters’.” On 5/2/1910, the same paper reported, “The County Commissioners…will convene…in the Hall of Records this morning. As far as could be learned last night nothing of grave importance is to come up for consideration…” Because records initially would have been stored in the courthouse and commissioners initially must have occupied offices in the courthouse, the construction of the Hall of Records in 1891 was probably necessary to relieve overcrowding there.

The architect who designed the Hall of Records remains unknown. F. P. Allen, who had designed the courthouse a little over a decade earlier, had moved from Walla Walla prior to 1891. Almost nothing could be located about the design and construction of the Hall of Records in the index to microfilmed old Walla Walla newspapers at the Whitman College Archives. The most revealing information came from newspapers in other cities. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer wrote on 5/5/1891, “The contract for the erection of a fire proof building 40×60 feet to be used as a hall of records for Walla Walla County was awarded to M. F. Butler [sic] for $27,585. The contract for a steam heating apparatus in the hall and courthouse was awarded to William Gardner for $6,250.” (“M.” F. Butler was in fact Norman F. Butler, a prolific Walla Walla contractor and landowner.) That same day the Spokane Review reported, “Today the county commissioners opened bids for construction of a fireproof structure to receive records. Six bids were received, ranging from $27,585 to $29,550, the first of which was from N. F. Butler, who was awarded the contract.” While there is no proof that Butler, who at times advertised himself as an architect, did not design the Hall of Records, there is equally no evidence to confirm that he did design it.

The Hall of Records is a one-story building with a hip roof. Unlike its neighbors that face West Main Street, it faces east toward 5th Street. No reference to construction materials was found, but the 1929 modification to the 1905 Sanborn Fire Map notes that its walls are pressed brick; the stucco plaster surface coating is not mentioned as it is not structural. The façade displays classical ornament, with a central massing to the (former) main entrance that projects slightly, as in the former County Jail building. The entrance is framed by a fairly narrow round arch and the surround has been formed to give an appearance of stone blocks, with a keystone at the top, above which is a small pediment containing the date 1891. The four corners of the building display quoins, purely decorative like the surround of the entry. A stringcourse surrounds the building and is almost as bold as the main cornice that has a delicate band of dentils. The most striking feature of this small building, however, must be the pairs of enormous hooded round arch windows that dominate the four surfaces, each of which measures 10½ feet high by 4½ feet wide. What inspired the architect to call for such large windows can only be conjectured at a time when most buildings continued to devote less square footage to the windows.

Resources

- Pioneer/Columbia Title

- Whitman Archives

- Lyman, Prof. William Dennison, History of Old Walla Walla County embracing Walla Walla, Columbia, Garfield and Asotin Counties, 1, S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, Chicago, 1918

- Gilbert, Frank T., Historic Sketches of Walla Walla, Whitman, Columbia and Garfield Counties, W.T. and Umatilla County, Oregon, G. Walling, Portland, Oregon, 1882

- City Directories (various years)

- Walla Walla Statesman (various dates)

- Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 5/5/1891

- Walla Walla Union (various dates)

- Spokane Review, 5/5/1891

- Michael Houser, State Architectural Historian, State of Washington DAHP

- Diane Reed, The Man Who Helped Build Walla Walla: the Local Legacy of Norman Francis Butler, Walla Walla Union-Bulletin, 4/26/1916

- Ron Branine, Facilities Manager, Walla Walla County

- Cindy Fazio, Walla Walla County Assessor’s Office

- Bennett, Robert A., Walla Walla: Portrait of a Western Town, 1804-1899, Pioneer Press, Inc. Walla Walla, 1980

- Bennett, Robert A., Walla Walla: a Town Built to be a City, 1900-1919, Pioneer Press Books, Walla Walla, 1982

- Sanborn Fire Maps, August 1884, March 1988, April 1894, 1905 and 1905 with July 1929 additions

- The California Architect and Building News, San Francisco, August 1882

- Judy Benzel, Walla Walla County Clerk’s Office

- The Library of Congress: Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers index

- Washington State County Courthouses Survey, Department of Archeology and Historic Preservation, Olympia, 2003

- Up-To-The-Times monthly magazine, Walla Walla, various issues 1914-1916

- Washington Standard, Olympia, 4/9/1880

- Taylor, Roger Bordeaux, The Building Legacy of Alexander Taylor in the Pacific Northwest, 1899-1944, 2002, Fresno, CA

- findagrave.com