A Wild Rose That Bloomed on College Creek

By Stephen Wilen, Walla Walla 2020 Historic Researcher, March 2018

The Formative Years: from Seminary to Four-Year College with a Conservatory of Music

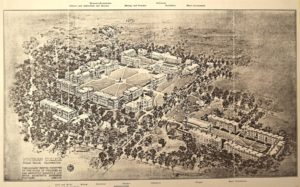

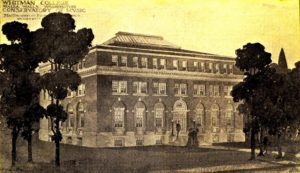

Perspective of the new conservatory by MacNaughton, Raymond & Lawrence, architects, Portland. Whitman Quarterly, Vol. 12, no. 2, 1909. Whitman Archives.

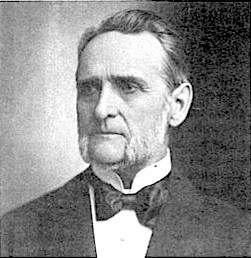

It was a dubious site, this place called Waiilatpu – “place of the rye grass” in Cailloux or Willetpoos, the Cayuse dialect – where he chose to erect a memorial to his friends, Dr. Marcus and Narcissa Prentiss Whitman. But that is precisely where Cushing Eells, Congregational missionary, wanted it – where the Whitmans had established their mission in 1836, and where they were massacred by the Cayuse on November 29, 1847. Thus, it was at this far off place of the rye grass where the Rev. Eells determined Whitman Seminary should be built in tribute to his slain colleagues.

Surely this man, unassailably saintly in the eyes of all who knew him, must have allowed a modicum of emotion to lead him to conclude that this would be a suitable location for a seminary, an area sparsely populated with settlers who might have school-age children to be enrolled (seminary denoted secondary education rather than a place where one studied for the ministry).

Washington Territory had only been created in 1854, a time when Walla Walla County stretched from the crest of the Cascade Mountains on the west to the crest of the Rocky Mountains on the east, encompassing all of present-day eastern Washington, Idaho and the western portion of Montana. The tiny town of Walla Walla, approximately eight miles east of Waiilatpu, was the county seat, and that was where the majority of new arrivals were settling.

Although it was chartered by the Territorial Legislature to begin operating in 1859, within a few years Cushing Eells was overruled in his wish to keep Whitman Seminary at Waiilatpu. Despite the fact that Walla Walla had grown into a rough town – a veritable den of horse thieves, prostitutes, robbers, drunks and other miscreants – it was concluded that a town was unlikely to ever grow up at Waiilatpu, while Walla Walla had a substantial number of potential school-age recruits for the seminary.

On June 6, 1866, Dr. Dorsey Singh Baker donated four acres of land along Boyer Avenue to the President and Trustees of Whitman Seminary, which significantly influenced where the seminary would be located. Later that year, the seminary moved into a newly-built simple wood frame structure of two stories surmounted by an octagonal lantern on what is now the southwest corner of Boyer Avenue and Park Street.

The Territorial Legislature, in November 1883, amended the original December 1859 charter to allow the establishment of Whitman College, authorizing it to grant four-year degrees. That year the new college began offering courses in music, initially limited to voice and piano.

The Whitman Conservatory of Music was established in 1885 by President Alexander Jay Anderson as a department of, but separate from, the college, offering three-year programs leading to a diploma in voice or piano. Courses in music theory, harmony and organ were also offered. Harlan J. Cozine, a graduate of the New England Conservatory of Music, was the department head, and piano students studied the “New England Conservatory method” of scales, sight reading, technical studies and the works of Bach, Mendelssohn and Chopin. Cozine established the Whitman Choral Society in the 1880s. Graduation requirements were rather lenient; students had to demonstrate only that they could obtain a certificate to teach in public schools in Washington Territory, that they were proficient in English, and that they had completed at least one year of French, German or Italian. Those wishing to pursue a course of study in the conservatory were admitted tuition-free, the only requirement being regular attendance in classes.

In its early years, the conservatory was not housed on campus, but was referred to as being “downtown,” a description lacking specificity. Instruction was provided to both those who wanted to pursue a career of teaching music, and amateurs who simply wanted to improve their performance level. The first and only off-campus listing for Whitman Conservatory in a Walla Walla City Directory did not appear until 1893, when the location was given as “315 3rd nr [near] Birch.” Also shown at that address were Jane Lasater, widow of James Lasater, and her two sons, Wiley and James who were both listed as “students Whitman.” The address for the Lasaters was given as “315 3rd e s [east side].” The 1894 Sanborn Fire Map shows nothing on the northeast corner of 3rd and Birch, but there is the footprint of a large dwelling on the east side of 3rd, second lot south of Birch. Because of low enrollment in the conservatory in those years, it is more than probable that the widow Lasater, who, with her late husband, an attorney, had resided at that address for several years, rented space to Whitman to house the music department, perhaps in exchange for free or reduced tuition for her two sons.

During these early years, conservatory recitals and concerts were presented at Small’s Opera House on the southeast corner of 2nd and Alder Streets, a mere two blocks from the Lasater house. The Whitman Conservatory Musical Society, during its first season in 1896, presented The Light of Asia, an 1886 oratorio by the American composer Dudley Buck.

* * *

The earliest deed recorded for a transaction of the property on what would eventually become the campus of Whitman College was recorded on December 23, 1859 that transferred “… to L. C. Kinney, his heirs and assigns (conveys)… half of a certain tract of land… consisting of about 150 acres, with all the buildings thereon…” granted by the Territory of Washington, County of Walla Walla, Thomas Wolf. The price was $250. A Certificate of Survey of this land was filed that same day by surveyor Hamet Hubbard Case, who had surveyed the original town site earlier that year.

Eventually, 40 of the 150 acres came into the possession of Dr. Dorsey Singh Baker, who, as noted above, on June 6, 1866 transferred four acres of this land to The President and Trustees of Whitman Seminary, a corporation, for the sum on one dollar.

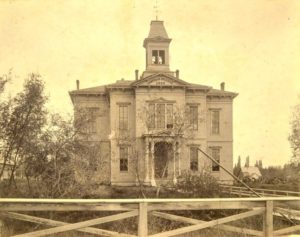

The first official building of Whitman College, College Hall, constructed in 1883, like the Whitman Seminary, was a two-story wooden structure that displayed somewhat more complex architectural embellishments than the simple seminary building. It was located east of the seminary building across College Creek, set back some distance from Boyer Avenue, in front of the current Prentiss Hall. This was Whitman College until the completion of the brick and sandstone Whitman Memorial Building in 1899 on the opposite side of Boyer Avenue.

The move from College Hall to the Whitman Memorial Building opened the door for the Conservatory of Music, a department of the college, but operating in a semi-autonomous fashion, to vacate Widow Lasater’s dwelling at 3rd and Birch and move into the former College Hall. And there it would remain until a new terra-cotta ornamented, red brick building designed expressly for the Conservatory of Music in Georgian Revival style was ready for occupancy in 1910.

When vacated in 1899, College Hall became the first on-campus home for the Whitman Conservatory of Music. Whitman Archives.

By the 1903-04 academic year it could be seen that the conservatory was developing more rapidly than had been expected. For 1905, 186 students were enrolled. By 1906, four degrees were offered: Diploma of the Conservatory; Normal Certificate; Certificate of the Conservatory; and Bachelor of Music. Interestingly, the 1909 college course catalog omitted any reference to a Conservatory of Music, instead referring to it as an “affiliated institution beneficial to the college, but not administered by the college faculty nor under its discipline.”

Up-To-The-Times noted in its December 1908 edition that Miss Gena Branscombe, instructor in pianoforte, gave a recital entirely of her own compositions, assisted by three other faculty members. It stated that, “The work of this talented composer has attracted much attention from musical critics throughout the United States and is generally acknowledged to be of unusual merit.” The same edition of this monthly magazine mentioned that Ossip Gabrilowitsch, the Russian-born American pianist and son-in-law of Samuel Clemens, aka Mark Twain, was scheduled to present a recital in the Whitman College chapel on April 20, 1909 under the auspices of the Whitman Conservatory. Also reported was that the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, including a chorus of 150, would appear at the Keylor Grand Theater in late May. One wonders what that program included – Beethoven, Brahms, perhaps even Mahler? The following November 27th, Fritz Kreisler performed there. It is remarkable in leafing through copies of Up-To-The-Times from the early years of the 20th century to note how many nationally- and internationally-renowned artists appeared in Walla Walla during that period, most often at the Keylor Grand.

Construction of the New Conservatory Building

Throughout the early decades of Whitman College, it was an ongoing struggle to maintain financial solvency. Traveling the country seeking funds to keep the college afloat took its toll on President Stephen B. L. Penrose, who assumed the presidency of Whitman in 1894, and kept him all too frequently from duties that he surely considered more critical than what was essentially begging for financial help. Payment of faculty salaries, not commensurate with those of other colleges and universities, were frequently deferred; yet most of the faculty, having faith in Whitman’s mission, suffered along in their penury.

During these troubling years, frequently Penrose availed himself of the sage advice of Dr. Daniel Kimball Pearsons of Chicago. D. K. Pearsons was a medical doctor who additionally was involved in finance. He was the director of the Chicago Chamber of Commerce at one time, a Christian, and benefactor of Congregational and Presbyterian institutions. He remained supportive of Penrose, though on occasions chiding him for plans he saw as misguided or detrimental to the stability of the college, in particular proposed large expenditures that would contribute to a mounting debt. Be that as it may, Pearsons did gift Whitman College $50,000 that enabled the construction of the conservatory building; this was to be his final gift to the college.

The relationship between D. K. Pearsons and Stephen B. L. Penrose would be fascinating to explore in depth; Pearsons’ letters to President Penrose are not nuanced. In one letter he saluted the president as “Old Boy Penrose,” signing off with this statement, “Whip the two girls for me,” surely with tongue in cheek. On March 15, 1911, he wrote, employing his typically unorthodox punctuation, “I find that – I shall have enough to carry me to the end after paying all my pledges on the 14 of April next, I shall be 91 on that day. (out of debt) No more annuities from you or anyone. Keep your money Truly D K Pearsons” On May 4th he followed with another letter, “No, never move the college stay right there, you belong there the college belongs there, I advise you to settle down to business and stop building castles, you have room enough, stick to Walla Walla Truly D K Pearsons” Whether the reference to “building castles” referred to the recently completed conservatory building or consideration being given around that time to moving Whitman College from Walla Walla to Spokane is not known. (Whitworth College did make the jump, relocating from Tacoma to Spokane in 1914.)

In 1907, President Penrose launched a prodigious plan labeled Greater Whitman. In an attempt to expand the reputation of the college as an exceptional institution of higher learning, it proclaimed Whitman to be “The Yale of the West.” The Portland architectural firm MacNaughton, Raymond & Lawrence was hired to design a comprehensive plan for the campus that would consist of a multiplicity of new buildings harmoniously grouped and designed in a Georgian Revival style (retaining the quasi-Romanesque Revival Memorial Hall, but razing all other older buildings). It was in fact a breath-taking plan in its scope, calculated to cost around $3,000,000, and ultimately doomed to fail. Dean Archer W. Hendrick was the primary mover behind the Greater Whitman project, in 1908 proposing a $600,000 campaign to raise money for two science buildings, three dormitories, a library, a chapel, a conservatory of music and a central heating plant.

President Penrose had stated as early as 1904, “I think without doubt [the Whitman Conservatory of Music] is the best on the Pacific Coast.” In 1907, he wrote, “If a modern conservatory was erected with a large concert hall, equipped with a pipe organ and grand piano, and with an adequate number of practice rooms, a local need would be met and the people of Walla Walla would have a convenient and attractive place for concerts and entertainments of many kinds.” In 1908, Penrose informed D. K. Pearsons that the Whitman Conservatory of Music would become a full-fledged school of music, offering a Bachelor of Music degree, but that it would continue to operate separately from the main college, noting that it was bringing money to the college coffers. Pearsons responded to Penrose as he had for many years, gifting Whitman College $50,000 to construct the proposed conservatory building. As noted above, this was his final gift to the college; Pearsons died three years later in 1912.

Because of his many years of support to Whitman College, some felt the new conservatory should be named Pearsons Hall. This was not to be, and no building on the campus has ever been named in honor of this early benefactor of Whitman College. (As recently as 1993, then-Whitman Archivist Lawrence Dodd appealed to the Board to rename the then-former conservatory building to honor D. K. Pearsons, but it was felt appropriate to honor a more recent donor to the college. There is a photo of Dr. Pearsons inside the entrance to the building.)

Conservatory faculty, however, were proving to be somewhat problematic to the president, taking up much of his time. Penrose felt that despite their talent, some of them were immature. He fired one faculty member in 1906, but the conservatory director at the time, Prof. S. Harrison Lovewell resigned in protest, unwittingly, it might be argued, fulfilling Penrose’s analysis of the situation. (Lovewell later reinstated himself, his pique evidently assuaged.) Edgar Fischer, the prodigiously talented violinist, resigned following a dispute with the trustees, and with his wife formed the competitive Fischer School of Music downtown.

Penrose wanted to raise the conservatory faculty salaries to ensure the “highest musical standards,” but the college faculty was not 100 percent supportive of this “stepsister” to Whitman College. The noted historian, Prof. W. D. Lyman, declared, “Generally speaking [the conservatory faculty] does little for the moral or social uplift of the students.”

By 1912, the Greater Whitman plan had collapsed. Indeed, that year First Congregational Church, under the ministry of the Rev. Dr. Raymond C. Brooks, who was also on the faculty of Whitman College, donated its building fund of more than $60,000, intended for a new church building, to Whitman to prevent foreclosure.

While the Greater Whitman plan was not realized, what was considered to be the first – and ultimately only – building of the grandiose plan was the new Whitman Conservatory of Music building, that came to fruition through D. K. Pearsons’ final gift to Whitman. In fact, a separate music building does not appear anywhere on the architects’ 1907 birds-eye view of the proposed Georgian Revival campus; the music conservatory most probably had been intended for inclusion in the Fine Arts, Architecture and Archeology Building. It is a residence for the college president that is depicted on the southwest corner of Boyer Avenue and Park Street in the birds-eye view of the campus.

* * *

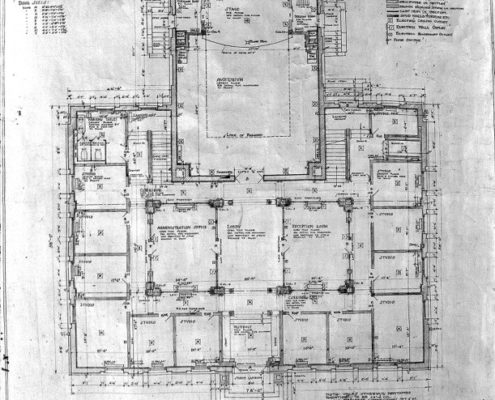

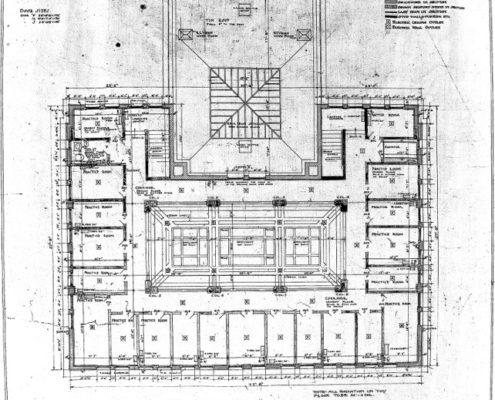

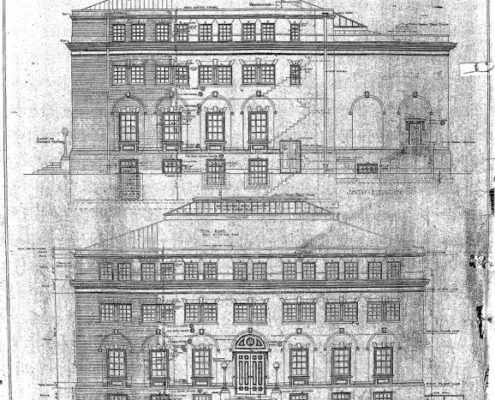

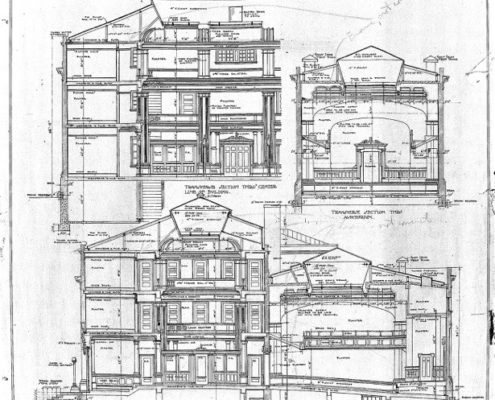

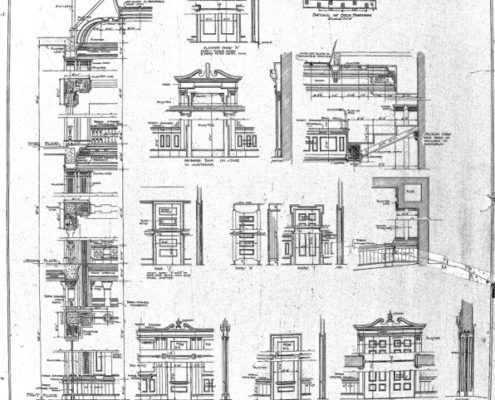

On March 15, 1909, the Walla Walla Union reported, Conservatory Plans Are Formally Adopted: Whitman Trustees Decide To Commence Immediate Construction of New Building, the ensuing article reading, “… plans for the new conservatory building to be erected at the corner of Boyer and Park streets where Prentiss hall now stands were formally adopted. [Prentiss Hall was the former Whitman Seminary building of 1866, to which a wing had been added to the rear in 1884. Following, it became known as Ladies Hall, the name being changed in 1902 to Prentiss Hall in honor of Narcissa Prentiss Whitman. In 1909, it was moved across College Creek to accommodate construction of the new conservatory building. It was razed in 1925.] The specifications call for a two-story [as built it was three stories] fire proof structure of re-inforced [sic] concrete to be built at an estimated cost of $50,000…”

The following May 18th, the Walla Walla Union included a headline, Conservatory Bids Are All Too High: Whitman College Trustees Open Bids But Reject Them As Being Above the Limit: Plans Are Returned To Architects In Portland For Revision: Bids Will Be Again Called For. The article went on to explain that all contractor bids were too high, and that MacNaughton, Raymond & Lawrence had been asked to make some modifications to their submitted proposal, following which advertisements would be placed for new bids.

Finally, on May 22, 1909, the Walla Walla Union proclaimed, Contract Let For New Conservatory: After Rejecting First Offers Committee Awards the Work To McLean: Will Take Charge Of Sub-Contracts, Guaranteeing That They Will Come Within Limits. Going on, the article stated that after consulting with the contractor and proposing that the college assume responsibility for the sub-contract work it was determined to follow that plan as preferable to reopening bidding.

The contract between J. A. McLean, whose impressive home stands on the northwest corner of Alvarado Terrace and North Clinton Street, and the Whitman College Board of Trustees was signed May 20, 1909.

The Walla Walla Union on May 30, 1909 ran an illustration of the projected conservatory captioned, “One of the finest structures in the entire city will be the new conservatory of music of Whitman College, permit for which was issued last week by Building Inspector William Metz. The estimated cost of the building is $50,000, and work is to be started within a short time…”

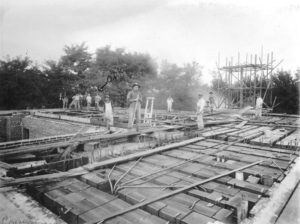

Laying floor joists, 1909. The initials ODK and arrow point to the popular Walla Walla contractor O. D. Kean, although he was not the contractor for this job. Whitman Archives.

Up-To-The-Times noted in August 1909, “The Whitman Conservatory of Music will be housed in a fine new $50,000 building this year. The construction is well under way; and as the first of the buildings of the Greater Whitman, will be watched with double interest… Prof. R. L. Schofield, who has been absent for a year, studying with Gurlmant in Paris [sic – Alexandre Guilmant was a renowned French organist and composer], will be back to teach the pipe organ and also the science of music… Elias Blum, of Boston, succeeds Prof. A. C. Jackson as head of the vocal department of the Conservatory… Abroad he [Blum] won the distinction of being the only American who ever led the Wiemar [sic] orchestra in Germany. He will also teach composition, being a composer of note…”

The following month, September 1909, Up-To-The-Times reported, “Work on the new Conservatory has been delayed by lack of material, but work is now being rushed night and day and it is hoped to have the first floor ready for work by the opening of the school. The work will then be completed on the other floors, which can be done without hindering the regular conservatory.”

The Whitman College Quarterly, v. 12, n. 2 (1909) noted, “In September 1909, the Conservatory will begin to enjoy the advantages of a large, fire-proof building devoted entirely to music. It is built of concrete, brick and terra-cotta, at a cost of over $50,000, and will be furnished with every convenience. Besides class-rooms, private studios, and a large number of practice-rooms, it contains a small concert-hall seating about two hundred and fifty people. It will have a full equipment of grand and upright pianos and of organs for practice.”

Under the headline, Building Nearly Done, the Walla Walla Union wrote on November 14, 1909, “The second term of the Whitman Conservatory of Music opens Thursday November 18. Never before in its history has the conservatory, say the officers of the school, had a more successful opening for the year. In spite of the inconvenience caused by the lack of room, the number of students has increased 25 per cent. The standard of work in all departments has been fully lived up to. The new conservatory, which when finished, will be one of the finest buildings in Walla Walla, is expected to be ready for use after the Christmas holidays. The work on the building is progressing rapidly.”

In December 1909, Up-To-The-Times, on a more optimistic note, recorded that, “The Whitman Conservatory of Music building, which has been in the course of construction for the past five months, is rapidly nearing completion, and will be ready for use on the first of the year. When completed it will be the finest music building in the Northwest, and one of which Whitman College and the city of Walla Walla may well be proud.”

On January 12, 1910, the Morning Union reported, Building To Open Feb. 2: Whitman Conservatory of Music To Occupy New Quarters Soon: Building Will Be Dedicated February 16 With Appropriate Exercises. Going on, the article stated,

“According to a statement given out by President S. B. L. Penrose yesterday afternoon, the Whitman Conservatory of Music will occupy its new quarters on the corner of Boyer avenue and Park street on February 2. That is the date of the beginning of the third term of work in the conservatory. The building has been in the process of construction for several months and when completed will be one of the most handsome buildings on the college campus. It is the first building constructed under the plans for the Greater Whitman. The architects are MacNaughton, Raymond & Lawrence of Portland and who maintain a branch office in Walla Walla.

The auditorium of the conservatory will be devoted exclusively to teaching. It will also contain the offices and reception rooms.

The second and third floors will be devoted exclusively to practice rooms… Each student will have an individual locker drawer in which all students’ music will be kept.

One of the most attractive features of the new home of the conservatory is the color scheme… which has been decided upon by the architects… The walls of the lobby will be… in delicate green, and the woodwork is ivory white…

A commodious basement… will [have] several recitation rooms… for teaching theoretical music and for ensemble work. An [Otis] elevator on the north side of the building will carry pianos to each floor from the tuning room in the basement…

The auditorium has been seated with open chairs and will seat about 250 people. A special fan ventilating apparatus has been installed in the auditorium which will insure [sic] plenty of fresh air…

There are 44 practice rooms… fourteen studios which will be used by the instructors… The basement has five classrooms for ensemble work…

The building is heated with steam with a vacuum system.”

Finally on February 10, 1910, the Morning Union wrote under the headline To Open Conservatory, “After it has been in the process of construction for many months the new Whitman Conservatory of Music will be opened for classwork Monday. Beginning today the pianos and musical instruments will be moved from Prentiss hall… into the new quarters. Although the exterior of the building has been completed for some time, the workmen have had much difficulty in getting the interior into shape for the use of the building. The inclement weather has been a great drawback in getting the plaster dry, and the painters and decorators have also complained of their inability to hurry on account of the coldness of the weather.”

Dedication of the Conservatory Building

The building finally entirely completed, the dedication ceremony of the new Whitman Conservatory of Music and MacDowell Hall was held February 17, 1910. The name MacDowell Hall was chosen for the conservatory’s concert hall to honor the American composer Edward MacDowell, with whom the conservatory’s director, Elias Blum, had had a cordial relationship.

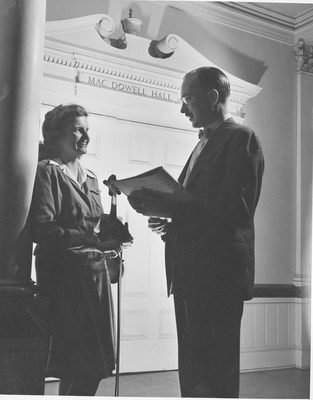

By the time of the conservatory’s dedication, the health of D. K. Pearsons, without whose generosity the building could not have been realized, did not allow him to attend. The firm of MacNaughton, Raymond & Lawrence had dissolved earlier in the year. Ellis Lawrence was the primary architect of the building and it was he who presented the keys to the new conservatory to Dr. Nelson Blalock, president of the Board of Trustees. The address, simply titled “Edward MacDowell,” was given by the Rev. Raymond C. Brooks, D. D. of First Congregational Church. Almost all of the music presented was by MacDowell, although Four Songs, op. 56 by director Blum was also included in the ceremony.

The most all-inclusive coverage of the dedication ceremonies appeared in Portland’s Sunday Oregonian on February 20th.

WHITMAN COLLEGE HONORS FOUNDER. Anniversary of Cushing Eells Birth and Semi-Centennial of School Observed.

MACDOWELL HALL OPENED. Building Costing $50,000 Dedicated at Walla Walla In Celebration Lasting Two Days. Many Prominent Men Attend. WALLA WALLA, Wash. Feb. 19. (Special.)

With the dedicatory services of MacDowell’s [sic] Hall, Whitman’s conservatory of music, the two days’ celebration of the semi-centennial of the founding of the college and the 100th anniversary of the birth of Cushing Eells was brought to a successful close Thursday. All of Walla Walla, the faculty, alumni, student body and board of overseers, which is comprised of the foremost men in the Northwest, took part in the ceremonies, which were beautiful in their simplicity. Never before in the history of the college had a more representative body gathered to pay homage to the memory of Cushing Eells, the man who founded the college and who did so much for the life of the Northwest. Many of the visitors returned to their respective homes at the close of the celebration, but quite a few stayed over to complete visits with friends or relatives.

Opening Services Wednesday. The presence of so many men identified with the life of the Northwest was the signal for entertaining, many dinners, both formal and informal, being given. The celebration opened Wednesday evening with the academic procession, in which the members, clad in the traditional cap and gown, filed slowly up the main aisle of the chapel in Memorial building and took places on the platform. The chapel was crowded. The other features of the evening’s programme were the musical exercises, which were in charge of Professor Ellas [sic] Blum, of the Whitman Conservatory of Music, and the addresses of Rev. Mark A. Matthews, of Seattle, and Right Rev. Frederick Keator, of Tacoma. President S. B. L. Penrose read a number of congratulatory letters received from educational institutions and prominent citizens of the entire country. It was 8:30 o’clock when the procession, marching to the Processional in A major, played by Professor R. L. Schofield on the great Roosevelt pipe organ, filed into the hall. Rev. Francis J. Van Horn, of Seattle, led in prayer. Dr. Matthews, the first speaker of the evening, was introduced by Judge Thomas Burke, of Seattle. He spoke on “Early Missionary Activity in the Northwest.” Bishop Keator took for his subject “Significance of Whitman College in the Life of the Northwest.” The opening session closed with the benediction of Rev. Samuel Greene, D.

Named for the Great Composer. MacDowell Hall was thronged Thursday afternoon when the dedicatory [service] opened. Rev. Raymond C. Brooks, pastor of the First Congregational Church of this city, made the principal address, on the life and character of Edward MacDowell, the great American composer, in whose honor the auditorium of the new conservatory was named. The readiness of this building for class work marks the completion of the first of the series of buildings which have been planned with the development of the “Greater Whitman.” The structure was constructed at a cost of over $50,000, and, though of modest outward appearance, is elaborately finished on the interior.

The total construction cost of the completed conservatory was actually $51,851; $2,500 in architect fees was included in this amount. The Oregonian’s dismissal of the building’s exterior as modest leaves room for debate. If any debate might be warranted, it would probably concern whether the dominant cavetto cornice above the second floor should have been switched with the lesser cornice above the third, or top, floor. One wonders why not one of the flattering reviews of the conservatory mentioned the two skylights, one above the large atrium and the other above MacDowell Hall, both with beautiful art glass at ceiling level.

* * *

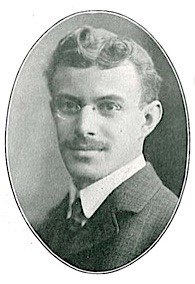

Elias Blum (1881-1957), who had joined the conservatory faculty in 1908 as instructor in voice, assumed the position of director in 1909. Blum was born in Eisdorf, Hungary of German parents. The family immigrated to the United States when Blum was ten years of age. Although he had no early musical training, he began composing at a young age, attracting the attention of American composers Arthur Foote, George Whitefield Chadwick and Edward MacDowell. He enrolled at the New England School of Music, eventually returning to Germany to teach at what is recorded as the Weimar Royal School of Music. After four years, Blum returned to Boston where he taught privately until accepting a position in the voice department of Whitman Conservatory in 1908. Blum was elected president of the Northwest Music Teachers Association in 1911. While at Whitman, in addition to voice, he taught composition and organ. He left Whitman in 1917 to assume a post at Grinnell College in Grinnell, Iowa, like Whitman another small Congregational sectarian college, retiring from Grinnell in 1944, remaining there for the balance of his life.

Blum was a composer of some note. Compiling a list of his compositions might prove daunting, but he wrote songs, as well as compositions for piano and organ, a number of which were performed by conservatory faculty and students. At least several of his compositions were published. His Passacaglia for Organ runs 22 pages in length!

One cannot help but be impressed by the caliber and quality of conservatory musical presentations under Elias Blum. In February 1910, a chamber music concert was devoted entirely to works of Beethoven. A multi-faculty, all-Schumann recital was given on March 15, 1910. On April 26, 1910, a faculty chamber music concert in MacDowell Hall was comprised entirely of works of the American composer Amy Beach, who was, needless to say, referred to at the time as Mrs. H. H. A. Beach (in earlier times, this talented composer was frequently referred to, primarily by music students, as Mrs. Ha Ha Beach). The following year, a second faculty chamber concert was devoted entirely to the works of another American composer, Arthur Foote. Both of these faculty presentations featured songs and compositions for strings and piano.

The Whitman Choral Society Founders’ Day Concert on February 16, 1911, held in the Whitman College Chapel on the third floor of the Whitman Memorial Building, presented Handel’s Messiah with Elias Blum conducting, Miss Marjorie Lyman, piano and Miss Rowena Ludwigs, organ. The same group on June 19, 1911, performed The Creation by Haydn in MacDowell Hall. Flowtow’s opera Martha was programmed in January 1913, Elias Blum again as conductor. In April 1917, Blum conducted Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis in the Whitman College chapel; prior to this work, Blum sang the Graduale from Mass in E-flat by Amy Beach, with violin obligato. Beach and Beethoven together in the remoteness of southeastern Washington in 1917 – almost more than the mind can contemplate.

Other major works performed during these early years included Mozart’s Requiem, Brahms’ German Requiem, Bach’s Christmas Oratorio and Mendelssohn’s Elijah, all in the Whitman College chapel with piano and organ accompaniment.

Finally, to back-shift a notch to lighter fare, in 1914, President S. B. L. Penrose wrote the words to what would become the Whitman song, Whitman! Here’s To You! The lyrics, bereft of a tune, were finally set to music by Elias Blum in 1917.

Up-To-The-Times included an article in its August 1910 edition regarding the conservatory that read, “Whitman Conservatory is planning for the biggest year it has ever had in the coming terms of 1910-1911. The new conservatory building, the completion of which hampered work last year, will be available from the very first of the term this fall, and the instructors will not be hampered from lack of room or equipment. The Whitman Conservatory is housed better, perhaps, than any other musical institution in the Northwest, and the new McDowell hall, in which are given the many concerts and recitals of the faculty and students of the institution, is admirably equipped for the purpose.”

In October 1910, it was announced that the Whitman Conservatory of Music had opened the year on September 20th with a number of registered students that “more than fulfilled expectations,” and that the “fine new conservatory building is in use” with “several concerts planned for the immediate future.”

Edward MacDowell died in 1908 and did not see his name consigned to the new conservatory concert hall. However, his widow, Marian MacDowell, visited Walla Walla in March 1916 while on a national concert and lecture tour to raise money for the MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire that was established in 1907. She gave a recital of her husband’s music in MacDowell Hall, followed by a reception. A program of the recital is in the Whitman Archives, on which someone penned copious notes, one of which described that following the recital a small girl approached Mrs. MacDowell and said with regard to her interpretation of To a Wild Rose from Ten Woodland Sketches, “But you played it too slow.” (Only To a Water Lily and Will O’ the Wisp from Woodland Sketches appear on the program. The prolific note scribbler penciled in To a Wild Rose, so perhaps Mrs. MacDowell decided to include it due to its popularity.)

The First Decades In the New Conservatory

The Whitman College Quarterly, v. 30, n. 3 for the academic year 1926-27 described the conservatory thus:

The conservatory occupies a handsome building devoted entirely to music. It is built of brick, concrete and terra cotta, and is fireproof. It contains private studios for teachers, classrooms, and a large number of practice-rooms. The auditorium, MacDowell Hall, has been named in honor of the eminent American composer, Edward MacDowell, and is a beautiful concert hall which seats about two-hundred and fifty [the hall had 149 seats on the main floor and 96 in the balcony, for a total of 245]. Its equipment includes a two-manual pipe organ.

The equipment is entirely new, comprising Chickering grand pianos for teachers’ studies and concert halls, and excellent upright pianos for practice rooms and class rooms.

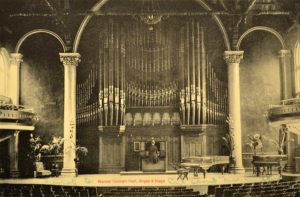

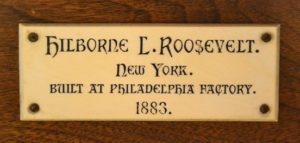

A very large and fine-toned pipe-organ is in the College Chapel. It was built by Hilborne Roosevelt in 1883 at an original cost of $12,500 and was rebuilt by the Marshall-Bennett Company in 1905. It has three manuals, and is unusually rich in flute and diapason effects. The total number of pipes is 2,058 [sic]. The compass of the manuals is 5 notes and of the pedals 30 notes.

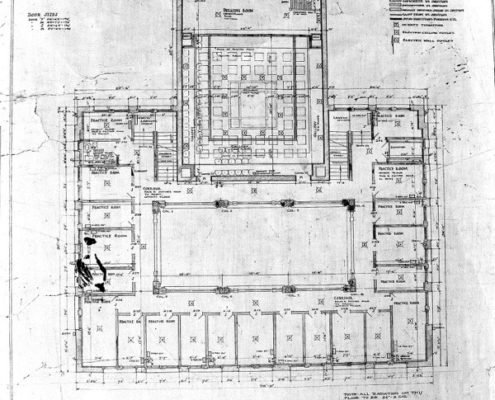

In fact, there was no pipe organ in MacDowell Hall when the building opened in 1910, as can be witnessed from photos of the hall that date to its first years. The 1909 blueprint for the main floor of the conservatory shows a room to stage left marked “Organ.” Thus, it would seem that this is where the pipes, chests – the mechanics of the organ – were to be located. However, no means of projection of the sound into the auditorium from this location is evident in early photos. Currently this space serves as the “green room” for performing artists.

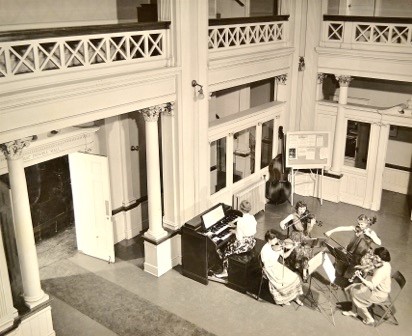

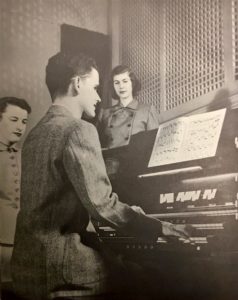

In this 1944 photo of MacDowell Hall, the pipe organ console may be seen in the front left corner. Turned balusters have replaced the former solid wall of the proscenium. Miss Esther Bienfang, who taught piano for many years, is giving instruction to two of her students. Whitman Archives.

Winifred Ringhoffer, ’50, who later returned to Whitman to teach voice, recalled taking organ lessons in the late 1940s, practicing on a two-manual pipe organ in MacDowell Hall. She stated that the organ’s console was located near the front left corner of the main floor. She also believes that the organ pipes might have been under the stage, a fascinating speculation because when MacDowell Hall was completed the wall across the proscenium from floor to stage was solid.

The 1909 blueprint for the conservatory basement notes the portion under the stage as “unexcavated.” Later, the proscenium wall was replaced by a row of turned balusters, a modification that would allow sound from organ pipes in the basement to project into the hall, lending credence to Prof. Ringhoffer’s recollection of the pipes being under the stage. A walk through the basement confirms it is excavated under the stage; a best guess is that the blueprint was modified to include full excavation when the building was constructed.

The Whitman College Quarterly, Conservatory of Music, v. 13, n. 2 (1910-1911) stated, “An excellent two-manual organ for instruction and practice will be installed in the new Conservatory building as soon as practicable.” This same statement was repeated in the Quarterly for 1911-1912, but by the 1913-1914 edition no mention of a teaching and practice organ was included.

Verification of this instrument was finally revealed in Conservatory Director Howard E. Pratt’s “Director’s Report to the Board of Overseers” in 1926, in which he wrote, “The installation of a modern two-manual pipe organ in MacDowell hall, this spring, is the principal addition to our equipment and is very much appreciated. This expense will justify itself.”

A Bennett three-manual organ console similar to the two-manual model that was installed in MacDowell Hall.

Working backward from this, two articles were located in Up-To-The-Times that reveal the mystery of this organ. In October 1925, the following appeared.

Whitman Conservatory of Music will soon have the second pipe organ for use of its pupils, a new two manuel [sic] Bennett organ having been ordered to be installed by Christmas. This will give pupils desiring to take that line of work a thing which has not been possible for the past year, with the one organ in Memorial hall. Miss Rowena Ludwigs is instructor in pipe organ.”

Christmas 1925 came and went without the organ having been installed. Up-To-The-Times reported in March 1926 under a headline TO BUY ORGAN, “Faculty recitals by Whitman conservatory instructors during the winter have been a source of pleasure to a large number of Walla Walla music lovers. A small sum has been charged for these this year, the proceeds going toward the installation of the new pipe organ for MacDowell Hall.”

The choice of the Bennett Organ Company of Rock Island, Illinois was a logical choice, as this company was successor, in 1927, of the former Marshall-Bennett Company, the firm that had brokered the purchase of the Roosevelt pipe organ in 1904. As the Depression deepened, the Bennett Organ Company filed for bankruptcy in 1930.

* * *

Instructor Esther Bienfang in her first floor studio with student Evalee Thompson, 1944. Whitman Archives.

The Whitman Conservatory of Music continued in the 1920s to operate under its own administration, employing its own teaching staff. Although separate from the college, President Penrose did participate in its management. In 1921, 400 were enrolled in the conservatory, leading one wag to refer to it as the “insane asylum,” presumably attributable to the noise emanating from the many practice rooms. By the mid-1920s, the conservatory included those seeking a Bachelor of Music as well as adults studying for a diploma in piano, voice or public school music, and children taking music lessons.

Howard Pratt became director of the conservatory in 1919, remaining so until his death in 1936. He advocated for expanding MacDowell Hall to a capacity of 600 so that the Keylor Grand Theater and the Whitman chapel would not have to be used for larger performances; this was ultimately not realized, perhaps due to the ensuing Depression. (Gounod’s Faust was presented at the Keylor Grand in March 1923. A news article described it as the Whitman Conservatory’s “most ambitious program to date, raising the music program to its highest level.”)

259 woman and 70 men were enrolled for the 1929-30 academic year, but the Depression that soon swept the nation caused the conservatory to suffer, music being considered a luxury.

An early photo of the atrium when it was used as office space. The middle pony walls with their graceful broken cornices were later removed. Whitman Archives.

Through the 1930s and 40s, there remained a resistance to incorporate the Whitman Conservatory of Music into the college as part of the liberal arts program because the conservatory was felt to be a reliable source of income from the community to the college, e.g., child and adult students, and as a source of training of musicians for community service in music, especially as church organists, that might be viewed as a throwback to the nineteenth-century concept of conservatories as being foremost a moral environment for religious musical training.

By the 1930s the Bachelor of Music degree was dropped, replaced by the Bachelor of Arts with major study in music. A Soloist’s and Teacher’s Diploma and a Public School Music Supervisor’s Certificate were also offered. By 1936, there were two venues: the Music Department and the Whitman Conservatory of Music.

In 1948, the conservatory began broadcasting student recitals live from MacDowell Hall every Friday evening on radio station KUJ. That year Whitman Conservatory became an associate member of the National Association of Schools of Music, the highest accredited college music agency in the United States. The conservatory looked forward to a review at the end of the following year for possible full membership. Also in the 1940s, the Museum of Northwest History that had been housed on the third floor of the conservatory vacated, freeing up additional needed practice rooms.

The Bachelor of Music degree was reinstated in 1953. Finally, in 1965, full integration of the conservatory and the college was established, offering both Bachelor of Music and the Bachelor of Arts degrees. The 1965-66 academic year was the last in which the conservatory had a director, Kenneth Schilling. Henceforth the Whitman Conservatory of Music, whose faculty 60 years earlier had been castigated by Prof. Lyman for moral turpitude, would be a fully integrated department of Whitman College.

Final Years as the Conservatory of Music

With the opening of the new Hall of Music in 1985 across College Creek facing Park Street, the old building ended its years as home of the Whitman Conservatory of Music. For the next twelve years, until 1997, it housed college offices, following which, during 1997-98, it was meticulously restored and renovated for use as the Center for Communication Arts and Technology. It was rededicated with a new name: Frances Geiger Hunter Conservatory. Sadly, the last vestige of any connection to the composer of To a Wild Rose was lost when MacDowell Hall was renamed Ruth Baker Kimball Theatre in recognition of her longstanding support to Whitman College. Happily, though, this grand building was saved – a rumor had circulated that one donor offered to underwrite construction costs of the new Hall of Music if the old conservatory were razed and the new building placed on the site – and MacDowell Hall under its new name continues to provide a venue for recitals and chamber music concerts by Whitman faculty and students.

Mary Shipman Penrose Endows Hilborne Roosevelt Pipe Organ to Whitman

There is considerable additional information in Whitman Archives on Whitman’s Roosevelt pipe organ, in particular articles that appeared in the newsletter, Northwest and Whitman College Archives, v. 14, 1991 and v. 15, 1992, presumably based on information compiled by the late Stanley Plummer, professor of organ from 1950 until retiring in 1981.

* * *

During the early years of Stephen Penrose’s presidency of Whitman College he looked eagerly to the day when there would be sufficient funds to construct, in his words, a “stone building” to augment the somewhat rag-tag collection of wooden structures. His vision was realized in 1899 through the generous gift of D. K. Pearsons that financed the construction of the Whitman Memorial Building, designed by Walla Walla architect George Washington Babcock.

Harrison Lovewell was hired in 1898 as director of the conservatory, teaching piano, pipe organ and the science of music. (He was also organist at the Methodist church.) As Whitman did not own a pipe organ in 1898, it is assumed that lessons and practice were arranged through a local church. In 1904, the college catalogue included information that organ lessons were being given using a pedal piano.

While visiting in the eastern United States in 1903, Lovewell began searching for a pipe organ for Whitman. He contacted the organist and composer William Horatio Clarke for help, and the following year Clarke wrote Lovewell that he had located a likely instrument, a Hilborne Roosevelt organ, built in 1883 for Christ Church Cathedral in Louisville, Kentucky. Christ Church Cathedral had purchased a larger organ, and the Roosevelt instrument was stored at the Marshall-Bennett pipe organ company in Moline, Illinois, where it had been rebuilt and was available for purchase. The original price of this organ as built in 1883 was $12,500; Marshall- Bennett offered the instrument to Whitman for $5,200.

As it happened, President Penrose recently had stated his desire to have a second “stone building” for Whitman, specifically a large chapel with a pipe organ that could seat 800. (A free-standing chapel was never built – the Greater Whitman proposal had included plans for a large chapel – and Whitman still lacks a true chapel. There was, however, a chapel of sorts on the third floor of the Whitman Memorial Building for decades.)

Despite financial difficulties, Whitman held in trust $5,000 for the purchase of an organ. However, Stephen Penrose’s wife, Mary (known widely as May), stepped in and prevented this expenditure to the college by paying for the organ herself in two installations of $1,815.95 and $4,684.05, enabling the return of the $5,000 to the general fund. The lavish gift of the organ by Mrs. Penrose was in memory of her mother, Mrs. Nathaniel Shipman of Hartford, Connecticut. (Shipping and installation costs may explain the total payment of $6,500.00.)

In February 1905, the first shipment of organ parts reached Walla Walla, arriving in two boxcars at the Northern Pacific depot on the 27th. The organ had to be lifted by block and tackle to the third level of the Whitman Memorial Building, where it was installed in the chapel, a space that, located under the roof beams, had a fairly low ceiling. It is not known if the organ had an ornamental case in the Louisville church, but it may be assumed that it was a more appealing installation than the limited confines of the bland Whitman chapel permitted. In fact, part of the lowered ceiling in the northeast corner of the chapel had to be cut out to accommodate the pipes, some of which were 23 feet, six inches tall. Pipes and chests were enclosed in a case of black walnut. At the height of seven feet an opening consisting of wood lattice over fabric allowed for projection of sound into the chapel. As the organ was a tracker (direct mechanical) action instrument, the console would have been built into the walnut case. An extensive search managed to locate just one photograph of the organ, taken in 1953, as it appeared in the chapel. It suggests that it was surely the instrument’s sound and not its appearance that contributed to the esteem in which it was held. President Penrose considered the housing of this great organ in the cramped location in the third floor of the Memorial Building temporary, continuing to aspire to eventually having a “stone chapel” to which the organ would be relocated.

The Roosevelt organ has been described variously as, “one of the finest on the Pacific Coast… exceeded in cost and size only by the great organ recently installed in the Chapel at Stanford” (Whitman College Pioneer, October 4, 1910); “one of the best organs ever brought to the Pacific Coast” (Morning Oregonian, September 21, 1904); “probably the most interesting organ of tracker origination” (The Tracker, January 1960); “…is said to be one of the most complete instruments in the Pacific States” (“The Organ,” an article in the Boston magazine Musician, March 1905); “the largest organ on the West Coast north of San Francisco” (uncredited comment); and in the opinion of the late Prof. Stanley Plummer, “the largest organ west of the Mississippi when it was installed.”

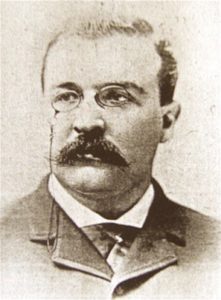

Hilborne Lewis Roosevelt (1849-1886), one of the preeminent organ builders in America during the 19th century, was a cousin of President Theodore Roosevelt, who, by coincidence, had given a speech in 1903 from the steps of the very building in which the Roosevelt organ was placed in 1905. From the photo of Hilborne Roosevelt, one can conclude beyond question there were strong genes in the Roosevelt family; he and the president could pass for twins. One wonders if hidden by his handlebar moustache was a set of big clickity choppers for which his cousin was famous. As a departure from his primary occupation, Hilborne Roosevelt and the conductor Leopold Damrosch were co-founders of the New York Symphony Society.

The Spokesman-Review in Spokane on April 12, 1905 described Whitman’s Roosevelt organ as being “practically the same as that at Oberlin College [located in Warner Concert Hall of the Oberlin Conservatory, building destroyed in the 1960s], which has been so widely advertised, and was made by the same factory. The organ has the same number of pipes and stops and each organ cost $12,500 when new.” There is some truth in this. Roosevelt’s Opus 93 was built in 1882. It was first installed in the home of W. S. Kimball of Rochester, New York, from whom it was purchased in 1904 – the very year Whitman was gifted its Roosevelt – for installation in Warner Concert Hall. Like the Whitman instrument, it was a three-manual (keyboard) organ, but was slightly larger, having 47 ranks (sets) of pipes with a pipe count of 2,350. It presented a flamboyant display of painted pipes stretching across the back of the raised stage platform in this quite large concert hall. (Oberlin’s Roosevelt organ was superseded by an E. M. Skinner organ in 1915, which in turn was completely rebuilt by the Holtkamp Organ Company of Cleveland. The instrument no longer exists.) Whitman’s Roosevelt, Opus 188, was built the following year for the Louisville church. It consisted of 39 ranks and 2,088 pipes. The Oberlin organ had a number of ethereal string ranks lacking in the Whitman instrument’s stoplist. Similarities? yes; sister organs? not quite.

Once the installation in the Whitman chapel was completed, Prof. S. Harrison Lovewell played the first recital for the Trustees the afternoon of April 15, 1905. The debut evening organ recital, played to a large audience, was on April 28th. One year later, April 15, 1906, Henry Hanchett of New York City, one of the founders of the American Guild of Organists, played an afternoon recital. The organ was used every morning for chapel, and for frequent recitals. For commencement in 1910, Prof. R. L. Schofield played a recital that “had a ‘Guilmant program,’ and the works of this modern composer were well illustrated.”

In the publication, Studies In Musical Education History and Aesthetics of the Music Teachers National Association in December 1914, an article by Conservatory Director Elias Blum titled “Music In the Pacific Northwest” included a statement that MacDowell Hall was fully equipped “with high-grade instruments, including a large Roosevelt pipe-organ.” His article also put the price of the conservatory at $60,000. Was this just careless reporting, perhaps tooting his horn over what had been accomplished during his term as director? One must wonder what caused him to be so incautious with the facts.

The Tracker, a quarterly magazine published by the Organ Historical Society, in January 1960 reported that the Whitman Roosevelt organ was hand-pumped when installed. Later, a 3.5 hp Orgoblo (electric) blower was added.

By the end of its first decade in the Whitman chapel, the Roosevelt organ was in need of repairs. A number of organ companies were contacted by conservatory director Elias Blum about servicing the organ, but the college did not have the funds to meet any of the bids received.

Maintenance of the organ during the ensuing decades is not recorded, but, as is the case with many churches that also do not have sufficient funds to keep their pipe organs in first-rate condition, Whitman probably did not always authorize funds for proper maintenance. Also not known is just how much the organ continued to be used during the 1920s through 1940s for recitals, instruction, student practice and chapel.

By 1950 the Roosevelt organ was only one-fourth operable. 1950 was also the year that Prof. Stanley Plummer arrived at Whitman, where he would remain for 31 years. Mary Penrose, by then a widow, consulted with Plummer about having the organ restored; he contacted the former Seattle organ builders Balcom & Vaughan, who submitted a bid of $10,000 to complete the work. Mrs. Penrose agreed to fund the full amount, and the work was completed by the fall of 1952, coming in somewhat below bid at $8,906.80. The work included the conversion of the organ from tracker to electro-pneumatic action. The original Roosevelt organ console was replaced with a used three-manual draw-knob console manufactured by the Reuter Organ Company of Lawrence, Kansas. The original Roosevelt console would have had a straight pedalboard. The Reuter console has concave radiating pedals.

Details of the entirety of work completed were not located, but an interesting requirement of Balcom & Vaughan was that Whitman burn or destroy everything discarded from the original 1905 installation, indicating that the case built for the pipes and chests might have been altered.

The rebuilt organ was dedicated October 19, 1952 with Stanley Plummer at the console. Mrs. Penrose’s health did not permit her to attend the recital, so a wire was run from the chapel to her home at 104 College Avenue just west of the Memorial Building so she could listen to a private broadcast. (College Avenue has since been renamed Penrose Avenue. The south termination of the street is now Isaacs Avenue, but formerly it extended south through the Whitman campus to Boyer Avenue.)

A 1953 photograph of the newly-installed console for the Roosevelt organ in the Whitman chapel. Whitman Archives.

The rebuilding and updating of the Roosevelt organ brought it to life once again. During the 1950s, Prof. Plummer played 105 recitals in the Whitman chapel. The British-born American organist E. Power Biggs, on a visit to Walla Walla in 1955, praised the organ for its originality. He marveled that it was intact as built, and not “chopped to pieces,” nor had it been enlarged, or that portions had been discarded. (Biggs was largely responsible for a resurgence of interest in the organ during the 1940s and 50s, but his comfort zone was more aligned with playing Buxtehude on a 17th-century Arp Schnitger organ than Elgar on an American Romantic organ, so his comments are noteworthy.) During the 1950s, Roosevelt organ recitals were broadcast over eight northwest radio stations.

With the completion of the Hall of Music in 1985 and a need for conversion of the chapel to office space, the Roosevelt organ was once again moved – the cost of the transfer a gift from the Whitman class of 1934 – this time to its current home in Catharine Chism Recital Hall in the Hall of Music, with chests and pipes located behind the scrims above the stage and the console, on a rolling platform, stored in a closet off-stage right. Prof. Plummer noted at the time that 95 percent of the original Roosevelt pipework was intact.

Although interest in organ study is undergoing a gradual resurgence among college/university/conservatory students, it has not fully recovered from the decline that occurred over the last decades of the 20th century. In the 1960s, Oberlin Conservatory employed four full-time organ instructors; it now has two. Whitman has no instructor for organ, with Dr. Kraig Scott of Walla Walla University providing instruction in organ as needed.

The number of Roosevelt pipe organs that survive more than a century after they were built is finite. Whitman’s Roosevelt instrument has not been used for a number of years. The console is deteriorated; the caps of the draw knobs, each of which represents a rank of pipes, easily fracture when touched. One can no longer “pull out all the stops” with vigor.

Despite its current neglected and unused status, it is hoped that the value of owning such a rare organ, even in its altered condition, is recognized and that at some point it may once again be returned to a functional state.

MacNaughton, Raymond & Lawrence

The Portland architectural firm MacNaughton, Raymond & Lawrence was short-lived, established in 1907, the year they designed the proposed Greater Whitman campus, and dissolving in 1910, the year the Whitman Conservatory of Music was dedicated. It is curious to consider that in such a short span how much work they designed for Walla Walla – most of which remained unbuilt – even opening a branch office in the Ransom Building at 1st and Alder under the supervision of one of their engineers, J. J Burling. Included among their unbuilt Walla Walla projects was a design for a large Beaux Arts style hotel to be called the Washington on the corner of 2nd and Rose, perhaps the very location where the Marcus Whitman Hotel stands, and elaborate gateposts for the Louis and Mabel Anderson mansion on Boyer Avenue, now Baker Center. In addition to the Whitman Conservatory of Music, the firm designed a house built in 1909 for Ben and Mary Stone at 1415 Modoc Street, frequently referred to as the “Frank Lloyd Wright house,” because it was based, at the clients’ request, on a Wright design that had appeared in Ladies Home Journal in 1906.

After 1910, Ernest MacNaughton (1880-1960) distinguished himself first as president of 1st National Bank of Oregon, later as president of The Oregonian newspaper, and ultimately becoming president of Reed College in Portland from 1948 to 1952.

Ellis F. Lawrence (1879-1946), a graduate of MIT, was the primary architect of the Whitman Conservatory building. He went on to enjoy a celebrated career as an architect. Following the dissolution of MacNaughton, Raymond & Lawrence, he formed a partnership with William Holford. They were retained by Whitman to design Penrose House, the first official president’s residence built for Stephen B. L. and Mary Penrose (1921, now the Whitman Admissions Office), Lyman House (1923), the heating plant (1923) and Prentiss Hall (1926). Technically not part of the Greater Whitman plan, the Georgian Revival style of both Lyman and Prentiss would have blended perfectly into the proposed layout

Lawrence was the founder, in 1914, and first dean of the School of Architecture and Allied Arts at the University of Oregon. He also established the Oregon Chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1911.

* * *

Following are several blueprints and elevations for the Whitman Conservatory. They have been inverted from white on blue to black on white for easier reading. It is interesting to note that each of the elevations is 90 degrees off from the orientation of the building, e.g., the front, or Boyer Avenue, elevation is labeled West Elevation when in fact it is the north elevation, and the side or west elevation that faces Park Street is labeled South Elevation. Was consideration at an early stage given to orienting the building to Park Street, or was this simply a draftsman’s error? Given that most Whitman buildings faced Boyer at that time, it was more than likely a mistake of the draftsman.

To conclude, several photographs from March 2018 give evidence to the quality of the restoration of the former Whitman Conservatory of Music building, now renamed Hunter Conservatory.

References

- Anderson, Florence Bennett, Leaven For the Frontier: the True Story of a Pioneer Educator, Christopher Publishing House, 195

- Bishop, Chris, Hunter Conservatory – From Music to Multimedia, Whitman Magazine, March 2014

- Brigham, Heidi, Music Librarian, Whitman College

- Dodd, Lawrence L., collected papers, Whitman Archives

- Edwards, G. Thomas, The Triumph of Tradition: The Emergence of Whitman College 1859-1924, Whitman College, 1992

- Edwards, G. Thomas, Tradition In a Turbulent Age: Whitman College 1925-1975, Whitman College, 2001

- McCaw, Kaitlyn, From Conservatory to Department of Music: The Evolution of Music And Morality at Whitman College, 2013

- Nye, Eugene M., “Old Tracker Organs of the West,” The Tracker magazine, January 1960

- Peterson, Mallory, The Whitman Conservatory of Music: Engendering Morality at Whitman College, 2011

- Plummer, Stanley, collected papers, Whitman Archives

- Ringhoffer, Winifred, Whitman Conservatory graduate (1950) and retired Whitman Conservatory faculty, telephone interview

- Stickles, Frances Copeland, Another Sort of Pioneer: Mary Shipman Penrose, Castle Island Publishing, 2007

- Warch, Willard, Our First 100 Years: A Brief History of the Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, Oberlin, Ohio, 1967

- Williams, Edward Franklin, The Life of Dr. D. K. Pearsons: Friend of the Small College and of Missions, Pilgrim Press, 1911

- Catalogue of Whitman College, 1908

- Catalogue of Whitman College, 1918

- City Directories, various years

- Grinnell College Bulletin, Grinnell, Iowa, March 1918

- Morning Union, various dates 1909-10

- Music and Musicians magazine, March 1917

- Northwest & Whitman College Archives, Penrose Library, multiple resource materials

- Northwest & Whitman College Archives newsletter, v. 14, 1991

- Northwest & Whitman College Archives newsletter, v. 15, 1992

- Organ Historical Society organ database, https://pipeorgandatabase.org/index.html

- Potter, Elisabeth Walton, “Ellis F. Lawrence (1879-1946),” oregonencyclopedia.org, last modified March 17, 2018, https://oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/lawrence_ellis_f_1879_1946_/

- Pioneer Title/Columbia Title

- Prabook, https://prabook.com/

- Sanborn Fire Maps, 1894 and 1905

- The Conservatory of Music, an unsigned, undated, typed manuscript

- The Developing Campus 1859-2002: Pictorial Review of Whitman College Buildings, Northwest & Whitman College Archives, 2003

- The Etude magazine, January 1913

- University of Oregon Libraries

- Up-To-The-Times magazine, 1909-1910 and 1925-1926 various dates, Walla Walla

- Waiilatpu, the Whitman annual, various years, 1940s-50s

- Walla Walla Union, 1909 various dates

- Whitman College Annual Report of the President, various years, 1940s-60s

- Whitman College Quarterly, v. 12, n. 2, 1909

- Whitman Quarterly, November 1985

- Wikipedia, “Hilborne Roosevelt,” last modified February 8, 2017, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hilborne_Roosevelt