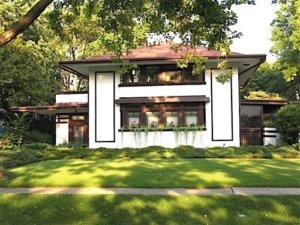

A Frank Lloyd Wright Prairie-style House Adapted for and Built in 1909 for Ben Gerard and Mary Paine Stone

Background

With a commitment to improve the quality of houses for middle-class Americans, in 1900 Edward Bok of the Curtis Publishing Company invited a selection of architects to submit designs for inexpensive homes. Selected plans would be published in the monthly magazine Ladies Home Journal. The late Frank Lloyd Wright biographer and longstanding architecture critic for New Yorker magazine, Brendan Gill, wrote that Bok was particularly interested in improving efficiency and hygiene for American houses. He advocated for sleeping porches, sanitary bathrooms and kitchens, and more compassionate dimensions for servants’ bedrooms. Most of the published plans could be purchased for as little as five dollars, enabling the buyer to construct an architect-designed house with a nominal financial output for a working set of plans. Ladies Home Journal continued publishing these commissioned designs for years.

Beginning in the 1930s, the monthly magazine Better Homes & Gardens began a similar practice, publishing first a monthly commissioned house design under the title “Bild-Cost” plans, and later by the more well known “Five Star” plans during the 1940s and 50s. (The author’s house was built to a “Five Star” plan, designed in 1953 by Omer Mithun and Harold Nesland, then practicing in Bellevue, Washington. The firm Mithun continues to maintain a large practice in Seattle.) Plans for “Five Star” homes often could be purchased for even less than those published in Ladies Home Journal.

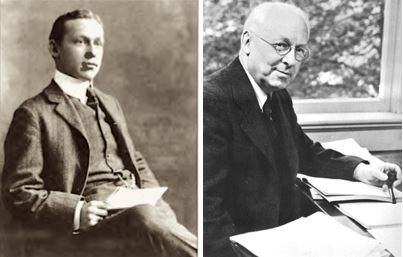

Among architects asked in 1900 to submit plans for Ladies Home Journal was the 33-year-old Oak Park, Illinois architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright’s first submission, titled A Home In A Prairie Town, was published in the February 1901 issue, followed in July 1901 by A Small House With “Lots of Room In It.” (It was decidedly not small.) Wright’s third submission to the magazine was published in April 1907, titled A Fireproof House for $5,000, with the disclaimer that the cost was based on the Chicago market price. It went on to state that Wright’s commission for furnishing a complete working set of blueprints for this house, including his involvement as construction supervisor, would be ten percent of the total cost to build the house. If Wright were not engaged to supervise, the fee would be seven and one-half percent of the total cost, but Wright specified he would insist that the client hire a competent construction supervisor for the job. These prices represented a significant increase over the 1901 five-dollar cost for plans.

A fourth Frank Lloyd Wright design for a home, his Opus 497, termed A Crystal House, appeared in Ladies Home Journal in June 1945.

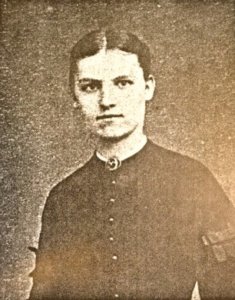

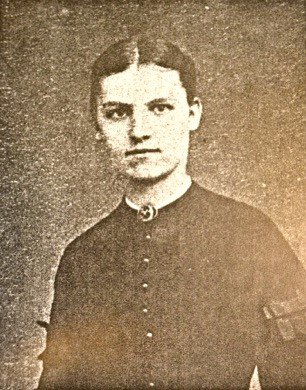

Mary Paine was born May 29, 1883, the middle of three surviving daughters of Mr. and Mrs. Frank Paine. Frank Paine was a founder of First National Bank, and an early Walla Walla councilman and mayor. He built the Paine Building at 2nd and Main in 1879 (extant), and served as superintendent of the Washington State Penitentiary, among numerous other accomplishments.

Mary Paine was perusing the April 1907 issue of Ladies Home Journal when she came across Wright’s design for the $5,000 fireproof house. The appearance of this house – unlike anything else found in Walla Walla – dazzled Miss Paine, and she considered that that was a house she might want for herself one day; she is reported to have been an early admirer of Wright’s work. As it came to be, within one and one-half years, Mary Paine would be wed to young Ben Gerard Stone, son of Henrietta and the late Benjamin Franklin (B. F.) Stone, wealthy Walla Walla landowners, and would be residing in Walla Walla’s only Frank Lloyd Wright-based home.

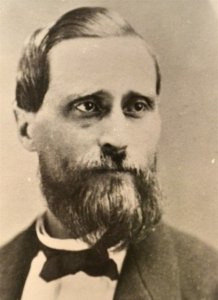

A Thumbnail History of the Stone Family

Despite being recorded in both Gilbert’s 1882 and Lyman’s 1918 histories of Walla Walla as one this city’s early leading plutocrats, there is not a wealth of local information available on Benjamin Franklin Stone. Much of what is included in this report was obtained from the Gregory Stone Genealogy, a 181-page hand-typed document painstakingly researched by Betty Meland Stone in 1979, a copy of which was most generously provided by Ben Gerard Stone, Jr.

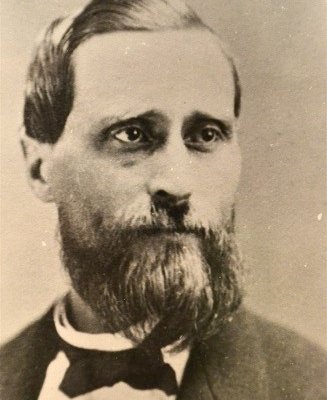

Benjamin Franklin Stone, who was known throughout his adult life as B. F. Stone, was born September 26, 1826 in Orford, New Hampshire. Local documents note that during 1850-51 he was a student at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. An older brother, Isaac, drawn by the gold rush fever of 1849 that followed the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848, traveled to California where all he caught was typhoid; he returned home in 1851. Despite Isaac’s failure to “strike it rich,” his trip inspired his younger brother, and B. F. sailed for San Francisco, crossing the Isthmus of Panama on foot before boarding a second ship, the New Orleans, from which he disembarked in San Francisco April 30, 1852.

It is alleged that B. F. Stone’s father gave each of his six sons $10,000 when they left home. ($10,000 in ca. 1850 would amount of somewhere near $330,000 today.) It is assumed that this is true, because while his years in California could not be documented, it is known that he had no success as a prospector, yet had plenty of money to buy into an established business in Walla Walla upon his arrival in 1858.

Just how or why B. F. traveled from California to Walla Walla is unclear, but it is known that he immediately bought into a local saloon run by W. A. Ball; he became co-owner with Ball of what was henceforth to be known as Ball & Stone Liquor Store, a rustic log cabin on what was then Nez Perce Street (the name was shortly changed to Main Street). After forming this partnership, it was probably Stone’s money that allowed Ball & Stone to add a wood floor to their rustic establishment, real doors and glass windows. Upscaled, the name was changed to Challenge Saloon, offering choice wines, liquors and cigars.

Following the discovery of gold in Orofino, Idaho in 1861, Ball and Stone got into the pack train business, eventually operating up to eleven trains between Walla Walla and the mining country in Idaho. B. F. Stone was acquainted with several local Indian chiefs through trading with them. He was a friend of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, who reportedly could “drink like a white man,” but who requested that Stone never sell liquor to his braves while they wintered near Wallula.

Stone was one of 44 who petitioned that the name Walla Walla be given to the new city; it was formally changed from Waiilatpu in November 1859. Following Walla Walla’s incorporation on January 11, 1862, Stone served as acting mayor until an election was held March 11, 1862. (Because he was only acting mayor for two months he is not listed among the mayors of Walla Walla. It is not known if he ran for the permanent position in March 1862.) He was one of the first five councilmen and was chosen President of the City Council April 10, 1862.

1862 was an active year for B. F. Stone. In addition to the above, he remained co-owner of the Challenge Saloon, operated as a wholesale grocer, was a freighter running pack trains between Walla Walla and Idaho, and was a moneylender. He also operated the first toll road across the Blue Mountains that he later sold for $10,000.

In 1863, B. F. Stone returned to Orford, New Hampshire, where he married Mary Anna Dean. B. F. and Anna (she preferred to use her middle name) had four children: George, born in 1864; Lewis, born in 1866 lived only nine days; Ida, born January 4, 1867; and Anna, born in 1868 survived just ten months.

In 1864, the Challenge Saloon was sold and Stone invested in several mining operations in Idaho. By 1869, he was a member of the executive committee of the Republican Territorial Convention for incorporators of the Walla Walla and Columbia River Railroad Company; two years later he was one of the original stockholders. That year, 1871, he was also an officer of the City Hall Association charged with building a hall to be used as a theater and for public gatherings.

On January 10, 1873, M. Anna Dean Stone died and is buried in Mountain View Cemetery alongside her two young children who predeceased her.

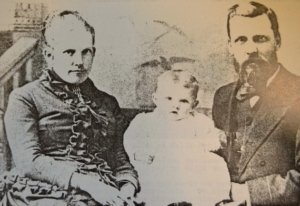

Henrietta Miller was born in Allen County, Ohio in 1848. Her parents were of German extraction, both highly educated. Her father, who had majored in horticulture in Germany, spoke five languages.

When she was four years of age, Henrietta’s family left Ohio by wagon train to settle in Oregon Territory, where her father became involved with horticulturist Seth Lewelling in developing the Bing cherry, a crossbred graft with the Black Republican cherry. The Bing was named for the Chinese Manchurian foreman, Ah Bing.

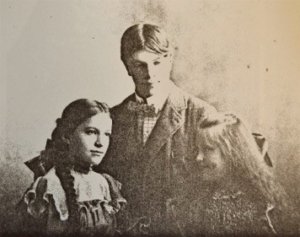

In 1854, Henrietta’s older sister Clementine got married and relocated to Walla Walla. Henrietta was sent to live with her sister, where she attended school and later taught school. Despite an age difference of 22 years, at some point Henrietta met B. F. Stone, and they wed in 1879. From this marriage, Ben Gerard Stone was the first born in 1880, followed by Ruth in 1884 and Edna in 1886.

B. F. Stone had amassed large parcels of land in and around Walla Walla and in Umatilla County. While married to Anna, they settled on land beyond the then-city limits of Walla Walla on South 2nd. Early listings for B. F. Stone in city directories were sporadic. His first listing did not occur until the 1893-94 edition that identified him as a capitalist, his residence noted to be “ws [west side] s 2nd 1 mi s city limits.” Frequently his name could only be found, if at all, under county residents, rather than with the City of Walla Walla listings.

Stone built a large house at this address probably in the late 1860s or early 70s that projected a simplified Greek Revival style. It was located approximately 100 feet west of present-day South 2nd slightly south of what is now Stone Street, and somewhat west of the current location of Christ Lutheran Church, the only house on a 160-acre parcel of land owned by Stone.

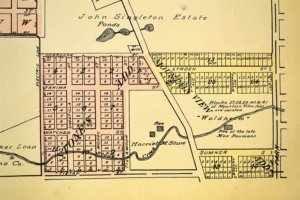

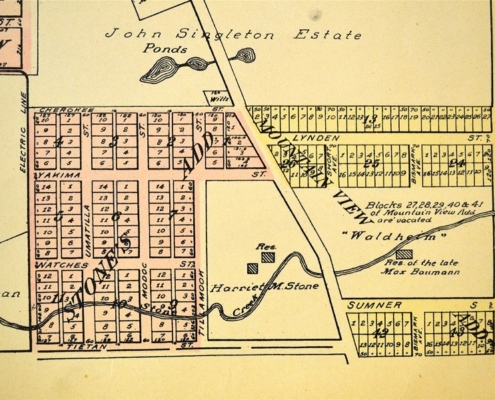

Shortly after his marriage to Henrietta, Stone remodeled and enlarged this house. On the first floor were a library, music room, living room, pantry, kitchen, utility room, several storage rooms and three fireplaces. The second floor contained five bedrooms, four bathrooms, two fireplaces, a storage room, and a maid’s room that included a bathroom. There were two main staircases; a third staircase at the rear of the house went to the attic. It was reportedly Walla Walla’s largest house at the time. It was not until 1909 that Henrietta Stone, by then a widow for a dozen years, had much of the 160 acres platted as Stone’s Addition to the City of Walla Walla, filed by Ben G. Stone for his mother on May 6th of that year. For some reason, the portion of this acreage on which her home was located, with its vast gardens and Stone Creek running across it, was never platted. Stone’s Addition includes 117 building lots spread over ten blocks. Mrs. Stone stipulated that the public should have full access to all streets, but she retained the right to lay water and sewer lines.

Henrietta Stone had been widowed upon her husband’s death November 12, 1897. She continued to live in the family home, where she raised her children, until her death January 1, 1931. As she aged, mobility became increasingly difficult, so in the mid-1920s she had a hand-powered elevator installed that was operated much like a dumb waiter. The house had one of Walla Walla’s first refrigerators that was a simple oak icebox connected to a compressor in the basement. The refrigerator, by then a relic, was moved to Ben and Mary Stone’s house following Henrietta’s death. The house on South 2nd is reported to have burned in 1943.

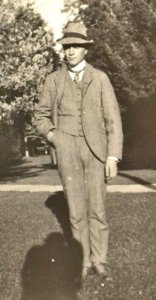

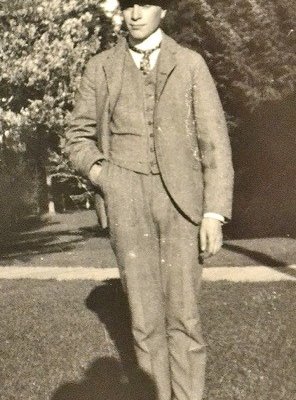

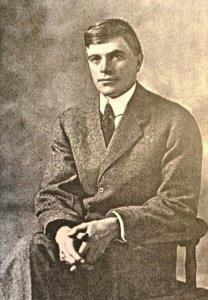

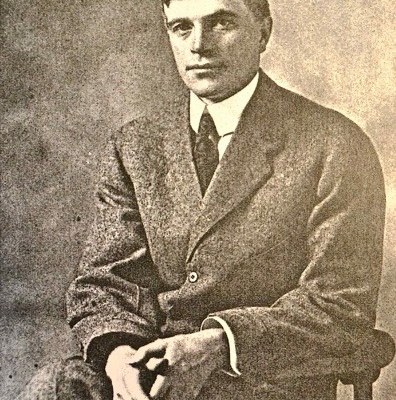

As a young adult, Ben Gerard Stone continued to live with his mother. While a student at Whitman College, he was accused of being one of several pranksters who put a cow in the Memorial Hall bell tower. If this oft-referenced prank is not just an urban legend, it might explain his hasty withdrawal from Whitman by his parents and transfer to Cornell University in New York State.

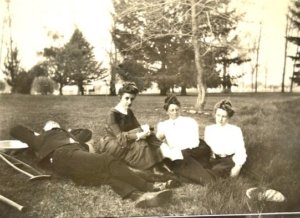

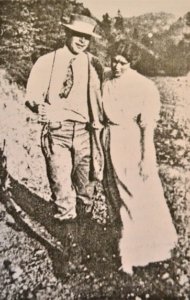

Ben Stone was an avid fisherman. He and Robert Moore, son of Miles Moore, the last Territorial Governor of Washington, were firm friends, and along with Ben’s best friend Charlie Campbell built a log cabin on the Walla Walla River in the Blue Mountains on government land, where they were known as squatters. He did not like to shoot big game, so when his friends went hunting Ben would go fishing. He was known as an expert fisherman, with all the right equipment.

Ben’s first listing in a city directory occurred in 1905, when he was noted to be a bookkeeper for Jones-Scott. William Jones was the husband of Ben’s half-sister Ida. In the 1908 directory he was listed as a farmer, a reasonable occupation for a young man who presumably oversaw at least portions of the vast acreage his father had accumulated, both in the heart of the city as well as in various parts throughout the county.

Ben Gerard Stone and Mary Paine became engaged in 1908. Mary was considered a “catch,” a young woman with a pleasing singing voice, who played the piano and who could roll off the correct botanical names of many flowers. On June 25, 1909, Henrietta Stone deeded a portion of the recently-platted Stone’s Addition to her son, described as “commencing 60 feet North of the Southwest corner of Lot 8 in Block 9 of Stone’s Addition to the City of Walla Walla; thence North 184.4 feet to the Northwest corner of Lot 10 in said block and addition; thence East 286 feet to the center line of Tillamook Street in said addition; thence South on the center line of said Tillamook Street 184.4 feet, thence West 286 feet to the place of beginning,” comprising approximately one acre. While it was not described as such, this could probably be considered a mother’s wedding gift to her son and his bride-to-be.

The Wedding That Led to the Construction of the House

The Evening Statesman on both October 27th and 28th, 1909 described the union of Ben G. Stone and Mary Paine, solemnized the evening of the 28th at 8 o’clock, as a “social eclipse.” Frances Paine, sister of the bride, was the maid of honor, and Charles Campbell, described as “the inseparable friend of the groom” served as best man. The wedding took place at the home of the bride’s parents at 351 Chase Avenue. Although it was noted that the Episcopalian ring ceremony was selected for the marriage, the officiant was the Rev. Dr. Raymond C. Brooks of First Congregational Church. (Brooks was also on the faculty of Whitman College.)

A small sampling of the many guests included Prof. Louis and Mabel Baker Anderson, Margaret Moore, Frank Moore, Mrs. B. L. Sharpstein, Minnie Sharpstein, Stuart Whitehouse, Mrs. G. W. Whitehouse, Melvin Rader, Mrs. C. M. Rader, Sarah Rees, Helen Ankeny, Josephine Paine Paul, and Charles R. Crawford.

The wedding was followed by a brief reception; then after changing their clothes the new bride and groom were driven by friends “in an automobile” to Pendleton.

Not to be eclipsed by the rival Statesman, the Morning Union, on October 31st, included the following far more comprehensive account of the evening.

“One of the most beautiful home weddings of the year took place Wednesday evening at the residence of Mr. and Mrs. F. W. Paine, 351 Chase avenue, when Miss Mary Paine became the wife of Ben Gerard Stone. The impressive ring service was used, Rev. Raymond C. Brooks officiating.

“Promptly at 8 o’clock, to the strains of the wedding march played by Miss Nettie Barr, the bridal procession proceeded down the stairs led by Mssrs. T. A. Paul and Robert Moore, groomsmen. Directly proceeding [sic] the bride, who was leaning on her father’s arm, came the Misses Ruth and Edna Stone as maids, and Miss Frances W. Paine, maid of honor. Charles Campbell stood up with the groom as best man.

“Only the personal friends of the couple attended the function, which was of the brightest of the social year. Immediately after the ceremony a short reception was held, when the newly wedded couple proceeded to their rooms and donned their traveling clothes. As the bride came down the stairs for the second time, she tossed her bouquet, which was caught by Miss Helen Snyder. As the crucial moment arrived and the bride’s cake was to be cut, the fates of several prominent young ladies present were decided. To Miss Marion Paxton fell the lot of the old maid, for she drew the thimble. Miss Hunt secured happiness by receiving the wishbone, while Miss Edna Stone was made happy by drawing the coin.

“The room decorations were simple and beautiful white effect being produced by the liberal use of snow drops and white chrysantheums [sic], while vines were draped from the corners of the room. Gorgeous bouquets of enormous chrysantheums [sic] were in evidence everywhere, and interspersed with pink roses.

“The gown that the bride wore was made from white crepe de chene [sic], while the maids wore pink of the same material. All carried roses, with the exception of the bride who wore a bunch of lilies of the valley, bound with white tulle. Refreshments of a choice nature were served to the guests, following which Mr. and Mrs. T. A. Paul took the young couple to Pendleton in an automobile, where they took the train this morning for Denver.”

It is plausible that the young couple moved in with Henrietta Stone on South 2nd for a time following their marriage. Under the Society column on December 18, 1909, the Evening Statesman noted that Mrs. B. F. Stone gave a reception “from 9 to 11 o’clock” at her home the previous evening, co-hosted by Mr. and Mrs. Frank Paine. The event was noted to be “one of the most fashionable events that occurred this season and a large crowd was present to pay their respects to the newly married couple.

The 1910-11 Walla Walla City Directory (© 1910) still listed Ben G. Stone as single and residing at “Stone’s addition” (Henrietta Stone’s house). The next edition, 1911-12 (© November 1911) correctly listed both Ben and Mary Stone residing at 1416 [sic] Modock [sic], with Ben employed as vice-president of Catton & Buffum, a wholesale fruit and produce house at 720 West Main Street that featured a prominent swastika on its signage.

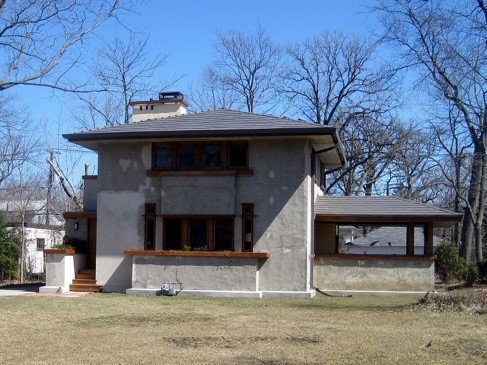

As far back as September 1909, it is likely that his then-fiancée may have inveigled her husband-to-be that their new home should be built to Wright’s 1907 design for a $5,000 fireproof house. On September 8th, Building Permit 601 was issued to Ben G. Stone to construct a house at 1416 Tillamook Street (at that time Tillamook Street continued south to West Tietan Street and was, in fact, the east boundary of their property; currently Tillamook terminates just south of Natches Street). Cost of construction was estimated to be $8,000, significantly higher than the $5,000 indicated by Frank Lloyd Wright in the 1907 Ladies Home Journal article. Nicholas Wierk, 1305 East Isaacs Avenue, was listed as contractor, ably assisted by his son, Nicholas, Jr., a carpenter.

With a valid building permit in hand in early September 1909, presumably a working set of blueprints, and his contractor lined up, construction of the house most likely commenced during that month. Although it was unlikely to have been occupied by the Stones before the end of the year, 1909 is a valid date for the major portion of its construction, though presumably it was sometime in 1910 before the new house was ready for occupancy by its young owners.

While the exterior of the house is reasonably faithful to what Wright designed, the young couple wanted a number of changes made to the plans specified by Wright.

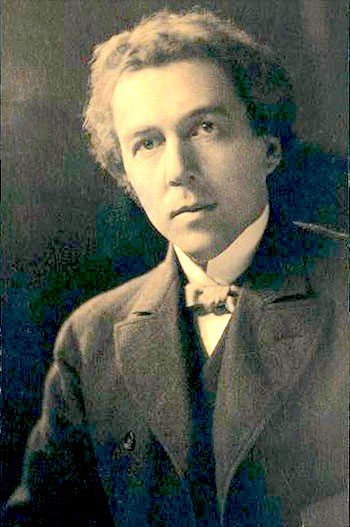

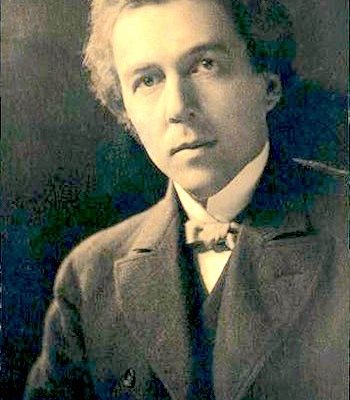

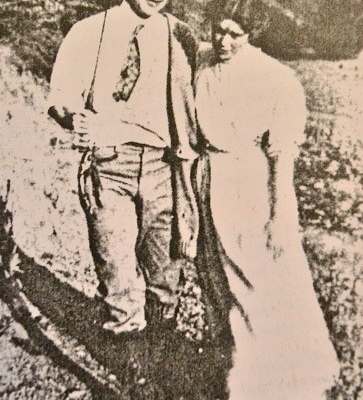

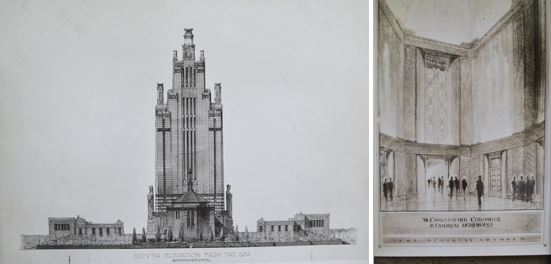

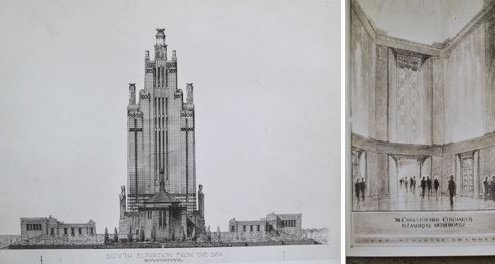

Enter Ellis Fuller Lawrence

In 1909, the Portland architectural firm MacNaughton, Raymond & Lawrence was actively involved in Walla Walla, having opened a branch office at 219 Ransom Building, with partner Ellis F. Lawrence assuming all work in Walla Walla, in association with J. J. Burling, a structural engineer. That year the firm – primarily Lawrence – designed a comprehensive and grandiose plan for the Whitman College campus called “Greater Whitman.” This plan, that featured a cluster of buildings in the Georgian Revival style, remained unbuilt due to the financial instability of the college, with the exception of one building that did not even appear in the original conception for “Greater Whitman,” the former Whitman Conservatory of Music (now restored and renamed Hunter Conservatory). Several other Walla Walla projects also remained unbuilt, presumably due to financial difficulties, including a grand, classically inspired Washington Hotel to be constructed on the northwest corner of 2nd and Rose where the Marcus Whitman Hotel eventually was built some two decades later.

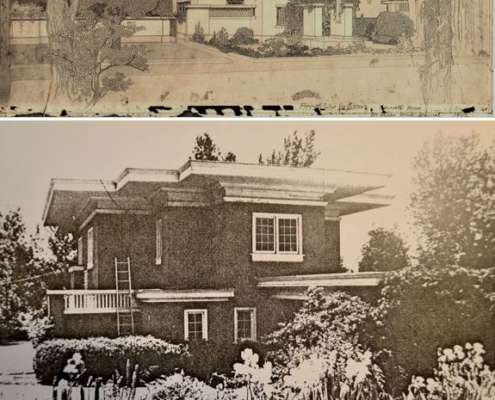

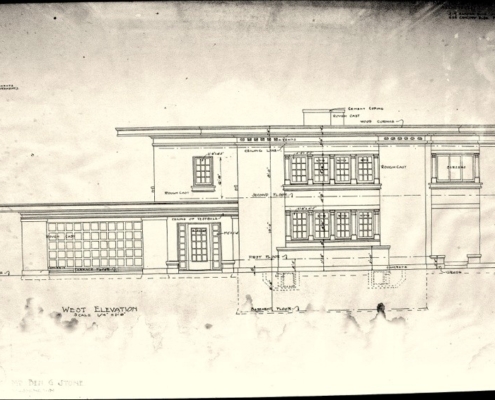

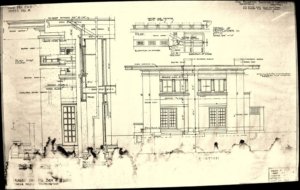

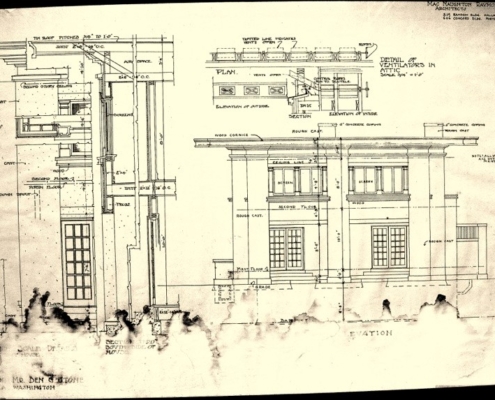

Ellis F. Lawrence was the partner who had been the primary architect of the conservatory building, like the Stone house also dating to 1909. As he had been given full charge of all residential design work for MacNaughton, Raymond & Lawrence, it was Lawrence who was retained by Ben Stone to modify Wright’s plans for the house Stone planned to build for his wife. Exterior changes were limited, although the prime concept of a fireproof house utilizing reinforced concrete for walls and roof was abandoned for what was a more utilitarian stucco plaster over wire-covered lath for the exterior. The centered chimney was designed by Wright to carry the load of the concrete slab floors and roof, a role lightened by the use of alternative materials in the Stone house. The wide roof overhangs as designed by Wright remain, as does the inward pitch of the roof that causes rainwater to drain to a center downspout in the chimney flue, so placed to prevent freezing in the winter.

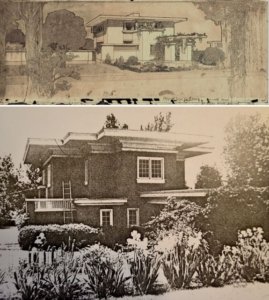

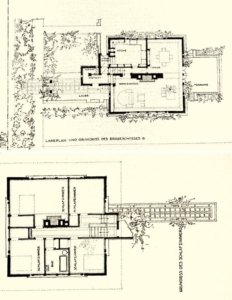

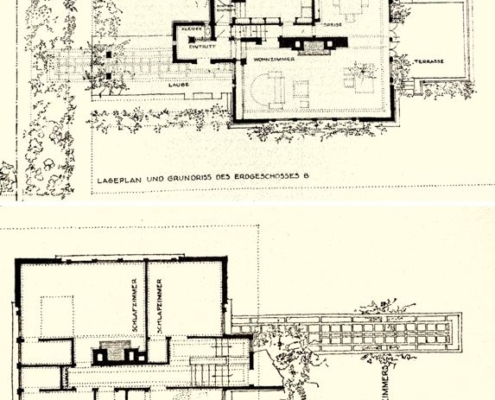

In 1909, Wright abandoned his wife and left for Germany with his mistress, remaining there until 1913 when he returned to the United States. During his time in Germany, two portfolios of his works, Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe von Frank Lloyd Wright, were published in Berlin in 1910, including several drawings of the fireproof house. As illustrated in the German publication, Wright specified that the house could be faced in one of two directions toward the street: a) with the entrance on the left side, as in the Stone house; or b) with the entrance pergola facing the street.

Wright called for airspace between the roof and the second floor ceiling. In the summer, air would circulate in this space by opening vents located beneath the roof overhangs, and would help keep the house cool. The vents could be opened and closed by a device reached from the second story windows. The Stone house retained this airspace to cool the house in the summer, but the system to open and close the vents, by ropes and pulleys accessed in the airspace, appears to differ from Wright’s idea (see vent detail in bottom illustration on Page 22).

Recall that Edward Bok of Curtis Publishing was an advocate of sleeping porches. On the right (south) side of the Stone house Lawrence added a nearly full-width sleeping porch on the second floor, accessed through both the master bedroom and the south rear bedroom. The floor of the sleeping porch slopes downward slightly from the house to allow for natural drainage of rain; the porch itself provides a year-round cover for the patio below, accessed through French doors that open off both the living and dining rooms. It is interesting to note that in the German illustration showing the pergola facing the street a patio is shown at the rear of the house, with access through doors in both the living and dining room. This was mirrored in the Stone house, with the “bonus” of a sleeping porch overhead.

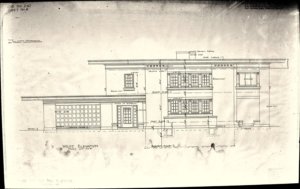

Wright’s design called for a lengthy, trellis-covered entryway to the front door, parallel to, but set back slightly from, the front of the house. In the German illustration of the plans for this house it is labeled Laube, pergola or summerhouse in English. In a drawing of the front elevation of the Stone residence dated July 20, 1909 by a draftsman with the initials LCR, Wright’s trellis approach can be seen with masonry supporting piers (see top illustration on Page 22). The completed house, however, did not include this feature, a porte-cochère having been substituted in its place.

Wright’s plan did not call for a garage, and the Stone house does not have a garage to this day – odd, as Ben Stone appears to have enjoyed stylish automobiles, and might have found a garage practical.

Frequently Wright hid the entrances to houses he designed. Those who have visited his famous Robie house of 1908-09 in Chicago may well have thought they had been directed to a servants’ entrance, so obscured is the front door. The entrance to the $5,000 fireproof house is tucked away on a side, though certainly not obscured to the degree that he hid the front door of the Robie house.

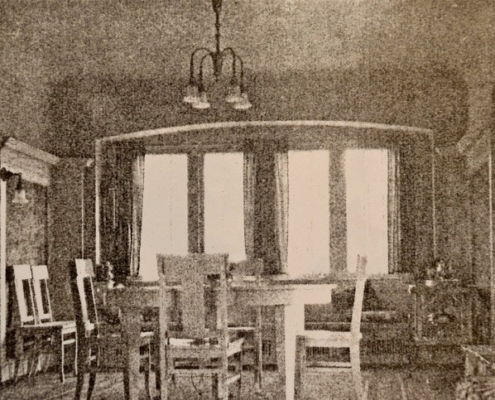

The floor plan of the house as designed by Wright was simple. There was no attic, no butler’s pantry, no back stairway; the design was, after all, aimed at middle class America. The main floor included an entry hall, large living room, dining room and kitchen, but no bathroom, although the plans show what appears to have been a washbasin in the closet off the entrance hall; the entrance hall was three steps below the level of the rest of the main floor in both Wright’s plan and the Stone house. The second floor contained four bedrooms and a single bathroom. Off the staircase landing was a small room for storage of trunks.

Interior modifications as made by Lawrence to Wright’s floor plan, were limited to the following. On the main floor a small bathroom is located where Wright specified a breezeway between the back door and the back yard; thus, there was no need to install a sink in the closet off the entrance hall. The trunk storage room is, in fact, located off the stairway landing, but this space projects outward somewhat more than in Wright’s plan, presumably to balance the similarly sized projection created by the sleeping porch on the opposite side of the house. This allowed Lawrence additional space in which to place the main floor bathroom.

The sleeping porch is set back from the main portion of the street façade the same distance as the entrance wing on the opposite side of the house, thus maintaining the symmetry of Wright’s design, which was for a perfectly square house with a slightly projecting entrance on the left side of the first floor. These side extensions give the Stone house a greater expanse to the front than Wright’s design. Lawrence had a well-defined sense of beauty and symmetry of design. Certainly not all of the buildings and houses he designed projected perfect symmetry, but those he designed for Whitman College – the aforementioned former Whitman Conservatory, and later, in partnership with William Holford, Lyman House, originally a boys’ dormitory; Prentiss Hall, planned as a girls’ dorm and to provide on-campus housing for sororities; and Penrose House, built as a residence for Whitman President Stephen B. L. and Mary Penrose – all reflect a central massing of their main façades.

On the second floor, the primary modifications are the addition of the sleeping porch, the conversion of the two bedrooms across the front of the house to a single large master bedroom, and relocating the full bathroom to the south side of the house between the master and a rear bedroom rather than between the two rear bedrooms as called for by Wright.

It is not clear whether Wright’s design for the fireproof house included a basement. The Stone house has a full basement, and original hot water radiators throughout the house remain functional. Wood for the two fireplaces would have been stored in the basement; thus a portion of a built-in wooden bench that spans the living room casement windows can be lifted, revealing a metal-lined dumb waiter by which wood could be brought from the basement to the living room via a system of ropes and pulleys. However, to stoke the fireplace in the master bedroom someone had to tote the wood up the staircase.

Wright specified that all interior walls be of metal lath plastered on both sides. In the Stone house, plaster over wood lath was used.

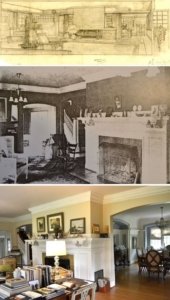

Although the exterior of the house was broadened to accommodate the clients’ wishes, overall it remains quite loyal to Wright’s design. The interior appointments, however, do not. Only one interior drawing by Wright of what he intended for the interior of the house could be located, in the collection of Wright’s drawings in the Avery Architectural Library at Columbia University. Happily, it depicts a perspective of the living room illustrating what appears to be a Roman brick-faced fireplace, the bricks above the fireplace opening being canted. Bookshelves are located on either side of the fireplace. Approximately eighteen inches from the ceiling is a shelf that probably was intended to surround the entire room and could be used for displaying artwork, vases, etc. An unconventional Wright-designed version of a grandfather clock can be seen on this shelf to the left of the fireplace. A glimpse of the staircase to the second floor is visible. At the far left of the living room is a grand piano, the case for which was obviously designed by the architect, as its shape is a segmented oval rather than the traditional kidney shape. (Current owners of the Stone house have a traditional grand piano in the same location as Wright’s living room floor plan placed his eccentrically-shaped grand.) A broad look into the dining room can be seen on the right, replete with a Wright-designed set of table and chairs, and a large armchair, decidedly uncomfortable looking, is in the foreground portion of the living room. The living room could be closed off from the dining room and the entrance hall by closing curtains hung on rods placed below the ornamental shelf.

It may never be known why Ben and Mary Stone decided not to follow Wright’s plan for the finishing of the interior spaces. One could conjecture that perhaps Ben gave in to his wife’s insistence on the Wright design for the exterior if Mary would consent to her husband’s demand for a more traditional interior, or that Wright’s interiors were just too étrange, or that the furniture he designed for the house looked positively backbreaking – as some have declared that it was! What Ellis Lawrence designed for the interiors is far more conservative, redolent of the stunning open atrium and theater of the Whitman Conservatory that he designed at the same time. The interior spaces remain intact almost entirely as built in 1909. The kitchen has been updated with care to not be jarring to the original feel of the house, and the first floor bathroom was enlarged by incorporating a portion of the closet off the entrance hall.

The registration form submitted on August 21, 1992 for placing Lawrence’s Women’s Memorial Quadrangle Ensemble on the University of Oregon campus on the National Register of Historic Places contains a statement that Lawrence was acquainted with Frank Lloyd Wright. It is highly doubtful that the Stones would have communicated directly with Wright about modifications they wished to make to his design, but it begs contemplating whether Ellis Lawrence might have written to Wright about this project – simply one more thing for which there probably is no answer. (Regrettably, no such correspondence could be located among the Ellis Fuller Lawrence papers at the University of Oregon Special Collections/Archives, nor could a vintage photo of the house be found either at the UO Archives or the Northwest and Whitman Archives.)

Occupancy History of the House From the Stones to Present

Ben G. Stone was only 29 years old when the house on Modoc Street was built. He was listed in the 1909-10 city directory as a real estate broker, at 9 South 2nd. That year, Stone, with Robert Allen and Whitman Professor Louis F. Anderson, filed articles of incorporation for the Walla Walla Realty Association. After a hiatus when he served as vice-president of Catton & Buffum, as noted above, Stone resumed involvement in both residential real estate and large parcels of undeveloped acreage. By 1915, he had formed a partnership with W. P. Lathrop as Stone & Lathrop at 5 South 2nd. They worked as financial agents providing insurance, mortgage loans, surety bonds, and dealt in real estate, most of which involved buying and selling ranches in Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana. In 1920, Stone was the Walla Walla branch manager of Jones-Scott Company, Inc. of Tacoma. He operated the business at 10 North 3rd, dealing in grain, coal, wood, building materials and fire insurance. In 1925, while remaining with Jones-Scott, he became secretary-treasurer of the Book Nook, located in Die Brucke Building at 1st and Main.

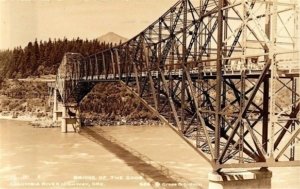

Ben Stone was one of a group of men who financed the Bridge of the Gods, a toll bridge over the Columbia River near Cascade Locks. Completed in 1926, the bridge was not popular because of the toll, and truckers occasionally stopped by 1415 Modoc to report missing or loose planks in the roadway. It has been noted that Ben frequently drove to the bridge to make repairs personally, hard to comprehend as the bridge is a multi-hour drive from Walla Walla. The State of Oregon eventually took over operation of the Bridge of the Gods.

Stone established Ben G. Stone Insurance, Surety Bonds and Investments in 1930, located at 12 South 2nd. He was the first insurance salesman in Walla Walla to offer a physician’s liability policy. In 1935, it was noted that he had become an agent for The Equitable Life Insurance Society. That year Mary’s and his son, Ben G. Stone, Jr. was a student at Whitman College.

Ben G. and Mary Paine Stone had a second son, Frank Paine Stone. Ben G. Stone, Sr. died November 5, 1945, aged 65. The following year, on August 6, 1946, Mary Paine Stone, “as Executrix of the Estate of Ben G. Stone, deceased, and Mary Paine Stone, a widow,” sold the house to Carl F. and Charlotte M. Jacky. The house remained in the Jacky family for 40 years. The year following sale of the house Mary moved to Spokane, but over the next decade she spent much time traveling. By 1955 she settled permanently back in Spokane, where she died December 7, 1965, aged 82.

On December 3, 1986, Gordon R., Richard C. and Lewis L. Jacky, “as tenants in common,” sold the house to George Drumheller and J. Dan Shea; they in turn sold it to Dr. David and Desiree Kellogg, the current owners, on January 21, 1992.

Denouement: Frank Lloyd Wright or Frank Lloyd Wrong

Is there an authentic Frank Lloyd Wright house in Walla Walla? From a technical standpoint, the answer to that question is no. However, one could certainly pettifog over this. There were a number of houses built throughout the United States in the years following 1907 that are documented to have been based on the fireproof house design featured in Ladies Home Journal in April 1907. It is ironic that the Stone house is not acknowledged anywhere – so far as could be ascertained – as a part of this group; arguably its exterior reflects Wright’s intention more authentically than several of the other such houses. In addition to considerable exterior alterations, all of those for which the roof can be viewed show a hipped rather than flat roof, and not one of them was built as fireproof, using instead stucco plaster over wood lath, as does the Stone house.

It must also be considered whether or not the Stones purchased a working set of blueprints from Wright, or whether they commissioned Ellis Lawrence to design their house based solely on what had been published in Ladies Home Journal. No interior views of how Wright intended the interior to be finished were depicted in the magazine article, which would explain Lawrence’s having full reign to embellish the interior spaces in a style in which he probably felt more comfortable.

The bulk of the exterior of the Stone house is more than passably true to Wright’s design, and Lawrence’s extensions at either side arguably reflect Wright’s doctrine for the prairie style house of harmonizing the house with its setting even more successfully than his own perfectly square design does; yet it is simply not what Wright designed. The interior is the most problematic in that it is Lawrence’s and not Wright’s design. (It could not be determined whether any of the other houses based on the fireproof house follow Wright’s design for the interior.)

In the end, neither the Stone house nor any of the other houses discovered in researching this report that were based on Wright’s 1907 fireproof house could be authenticated as bona fide designs of Frank Lloyd Wright because they were not constructed adhering one-hundred percent to the architect’s plans – and Wright himself would not have authenticated any of them with one of his Cherokee red tiles displaying his initials. There are only three Frank Lloyd Wright houses in Washington State, all from several decades later than the Stone house.

None of this, however, diminishes the fact that the Stone house is a stunning creation and remains, over a century after it was built, like nothing else in Walla Walla. Its placement on expansive grounds with many full-growth trees and Stone Creek flowing through the property south of the house might have pleased Wright. Walla Wallans may – and no doubt will – continue to refer to this house with pride as “the Frank Lloyd Wright house.”

Brief Biography of Ellis Fuller Lawrence

Ellis F. Lawrence was born in Malden, Massachusetts in 1879. He earned both his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Architecture from MIT in 1902. He travelled to the west coast in 1906, intending to establish a practice in San Francisco. En route, he stopped in Portland to visit his friend E. B. MacNaughton, during which the 1906 San Francisco earthquake occurred. This caused him to change his plans for San Francisco, and he decided to remain in Portland, becoming a partner in the firm of MacNaughton, Raymond & Lawrence.

Lawrence went on to enjoy a celebrated career as an architect. Following the dissolution of MacNaughton, Raymond & Lawrence, he formed a partnership with William Holford. Lawrence & Holford was retained by Whitman to design Penrose House, the first official president’s residence built for Stephen B. L. and Mary Penrose (1921, now the Whitman Admissions Office), Lyman House (1923), the heating plant (1923) and Prentiss Hall (1926). Technically not part of the Greater Whitman plan, the Georgian Revival style of both Lyman and Prentiss would have blended perfectly into the Greater Whitman proposal.

Lawrence was the founder, in 1914, and first dean of the School of Architecture and Allied Arts at the University of Oregon. He also established the Oregon Chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1911. He was acquainted not only with Frank Lloyd Wright, who once commented, with regard to one of Lawrence’s buildings, that he just missed being one of the great modernist architects, but also with the renowned arts and crafts architect Bernard Maybeck in California and landscape architect John Olmstead in Massachusetts. Although teaching in Eugene, he retained a family home throughout his life in Portland.

Lawrence was president of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture 1932 to 1934, and was involved in the organization of the Portland Architectural Club and the Architectural League of the Pacific Coast. He died in Eugene in 1946, aged 66.

Resources

Although many resources were helpful in compiling information for this report, special acknowledgement is due Dr. David and Desiree Kellogg, who have owned and lived in the Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired house since 1992, not only for opening their house to me, but for their patience for the year it has taken to sort through and formulate the information into this report.

I also wish to express deep appreciation to Ben Gerard Stone, Jr. of Santa Rosa, CA, of whom I was unaware until mid-July 2019 when a fortuitous email he sent to Walla Walla 2020 that was forwarded to me resulted in the beginning of a cyber acquaintance. Ben is the third-generation Ben Gerard Stone, and the fourth to carry the name Ben if his great-grandfather, Benjamin Franklin (B. F.) Stone is counted. His gift of two volumes on Stone and Paine genealogy was a surprise, and proved more helpful than could have been anticipated.

List of Sources:

- Whitman College and Northwest Archives

- Walla Walla City Directories, various years

- Walla Walla Evening Statesman newspaper articles, various dates

- Walla Walla Union-Bulletin, 11/5/1945

- Pioneer/Columbia Title archived deeds

- Gill, Brendan, Many Masks: A Life of Frank Lloyd Wright, Random House, New York, 1987

- Andres, Penny, Walla Walla: Her Historic Homes, Vol. 1, Walla Walla, 1991

- Storrer, William Allin, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, MIT Press, 1974

- Gilbert, Frank T., Historic Sketches of Walla Walla, Whitman, Columbia & Garfield Counties, W. T., Also Umatilla County, Oregon, Portland, 1882

- Lyman, Prof. William D., Lyman’s History of Old Walla Walla County Embracing Walla Walla, Columbia, Garfield and Asotin Counties, Vols. 1 & 2, S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, Chicago, 1918

- Shelley Hayreh, Archivist, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York

- Margaret Smithglass, Registrar/Digital Content Librarian, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

- Margo Stipe, Director and Curator of Collections, Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, AZ

- Bruce Tabb, Associate Professor, Rare Books Curator and Public Services Librarian, University of Oregon Libraries

- Harmony in Diversity: the Architecture and Teachings of Ellis F. Lawrence, an exhibit mounted at the University of Oregon in 1989 and at the Sheehan Gallery, Whitman College, in 1990

- Goldberger, Paul, The Art of Building on Paper in The New York Times Magazine, June 5, 1977

- Stone, Betty Meland, The Gregory Stone Genealogy, August 1979

- Susan Monahan, Walla Walla historian

- Skolnik, Theo, Wright Published In Ladies Home Journal, online chapter, worldhistoryproject.org

- National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for Women’s Memorial Quadrangle Ensemble, University of Oregon, 8/21/1992

- Wright, Frank Lloyd, A Fireproof House for $5,000, Ladies Home Journal, April 1907

- Wright, Frank Lloyd, Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe von Frank Lloyd Wright, Verlag Ernst Wasmuth Tübingen, Berlin, 1910, reprinted 1986

- Tsong, Nicole, Buying the Wright House, Walla Walla Union-Bulletin, 2/25/2001

- United States Census Records, various years

- The Architecture of the University of Oregon: A History, Bibliography and Research Guide: Ellis F. Lawrence, University of Oregon online, 6/20/2006

- Schellenbarger, Michael, editor, Harmony In Diversity: The Architecture and Teaching of Ellis F. Lawrence, School of Architecture and Allied Arts, University of Oregon, Eugene, 1989

- City of Walla Walla, Mountain View Cemetery records

- Standard Atlas of Walla Walla County, Washington, Including A Platbook of Villages, Cities and Townships of the County, George A. Ogle, Chicago, 1909

- The Western Architect, Minneapolis, January 1910

Addendum

In attempting to locate other houses in the United States that may have been built to Frank Lloyd Wright’s plan for a $5,000 Fireproof House, several were located. A few of the better ones illustrate this report. Although a subject no doubt open to debate, it is fair to say that probably not one of these could be said to be significantly more faithful to Wright’s design than the one Fuller modified for the Stones in 1909. One wonders how three came to be built in Glencoe, Illinois.