An Imposing New Temple for Walla Walla’s Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, Lodge 287

By Stephen Wilen, Walla Walla 2020 Historic Researcher, December 2017

Part 1: Construction and Dedication of the New Temple

A line drawing of architect Carl L. Linde’s proposal for the new Elks’ Temple, as published in Up-To-The-Times, April 1912. Note the drawing depicts a building of just four stories.

In his 1918 History of Old Walla Walla County, Vol. 1, Whitman Prof. W. D. Lyman wrote, “Perhaps most rapid in growth of all the [fraternal] orders in Walla Walla has been the Elks. The Walla Walla lodge of Elks No. 287 was organized August 10, 1894, with fifteen members. After a slow growth of a number of years the fraternity took on a swift development and at the date of this publication the membership exceeds six hundred. The lodge possesses one of the most beautiful buildings in the city, dedicated with a series of appropriate ceremonies and entertainments on May 23, 24 and 25, 1913.”

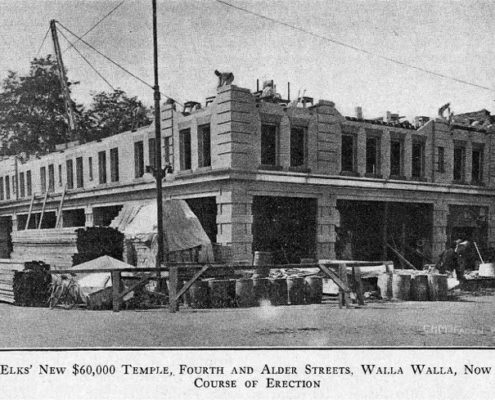

In the years leading up to the decision to erect a new temple, the Elks continued to meet in the I.O.O.F. Hall at 225½ West Main Street just east of the old court house. There is an existing photograph of Elks members seated on the multiplicity of steps leading up to the court house, perhaps the only place that provided sufficient light and space for such a large group photo. It was becoming apparent that the Elks needed a building of their own; however, nearly four years transpired from their initial resolve to construct a new temple until the dedication of the completed grand edifice. The first priority was site selection. The officers of the lodge eventually settled on a parcel at the northwest corner of Fourth and Alder Streets, comprising the south one-half of Lots 9 and 10 of Block 10 of the original City of Walla Walla. This property measured 110 feet on Alder and 60 feet on Fourth. The Sanborn Fire Map of 1905 shows two dwellings, a frame structure offering board and lodgings and a small store already on the property. The $14,000 purchase from Katie Butz, a widow who owned the land, was filed January 24, 1910.

The pending transaction had already been scooped and reported on January 20th in the Morning Union, under the headline Elks Buy Corner, that the Elks planned to erect a temple of approximately $100,000. In journalistic hyperbole, it went on to declare that the new temple would be five or six stories, that the first three stories were already rented, and the upper two floors would be for the Elks’ use. Seven months earlier, on May 5, 1909, the Morning Union had reported the following: Five Story Elks Temple Assured: Local Lodge Decides To Erect Large Structure This Summer: $50,000 Subscribed In Stock Last Night – Committee to Report Next Meeting. Continuing, the article stated that final action was pending regarding site selection and the new building would be well underway by September.

If neither of these news accounts proved to be 100 percent accurate, a course had been set by the Elks that in 1913 would result in one of the handsomest Elks’ Temples in the Pacific Northwest. And if the Morning Union was guilty in January 1910 of a bit of hyperbole in its reporting, Up-To-The-Times was not quite up to the times in its story in the February 1912 issue that announced, “The Elks Lodge of Walla Walla is planning the erection of a new building and club house. A site at the corner of Fourth and Alder streets is one of the most popular ones spoken of for the location of the new building.”

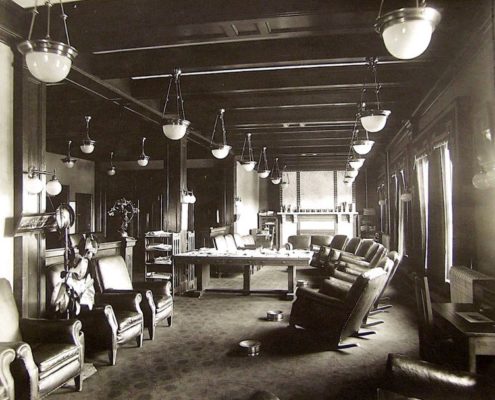

Once the site had been established, retaining an architect for the building would have been the next priority. Something comparable to what currently is referred to as a Request for Proposal was most likely published in area newspapers and architectural journals, specifying required needs of the Elks, whether to construct a four- or five-story building to best meet their requirements, and the amount of funds available to expend on the structure. The Walla Walla Union on February 1, 1912 wrote under the title Elks Receive Building Plan: Portland Architects Submit Drawings to Committee on Proposed New Temple, “Yesterday was the last day of time allotted by the Elks’ lodge building committee for the presentation of… plans… but by request the time has been extended three days… The last day brought architect McLaren and a representation from the firm of Linde & Ulrich from Portland with new plans…The committee is busy considering these various plans but have not arrived at no [sic] decision whatever…” On February 6th, the Walla Walla Union reported in an article titled One Of Three Plans Will Be Chosen Tonight: Elks’ Building Committee To Announce Decision on New Structure – Assured Building of 4 or 5 Stories, that “the final decision has been narrowed down to three sets of plans.” The article continued that the committee needed to reach a decision as to whether the building would be 100 percent for use of the Elks or if it would be a combination of stores and offices with space for the Elks. “One floor will be devoted to a sort of club, recreation room and sleeping rooms for lodge members only, having shower baths, billiard and card rooms, reception parlors and other features… [they] are in favor of going the limit rather than regret a smaller structure later.”

The following day the Walla Walla Union, in an article with the wordy title, Elks To Build A Modern Four Story Building: Make Final Choice of Plans at Meeting of Lodge Last Night: Building Will Cost Approximately $75,000: Roof Garden Still Undecided – First Floor to be Rented for Stores – Second for Dormitory, Third for Club, Fourth for Lodge Rooms noted that, “The building committee… had the plans narrowed down to those of three architects before the meeting, and… the plans thought to be best… were those submitted by Linde & Ulrich of Portland.” It went on to note that the second floor would contain ten to fifteen suites of rooms for bachelor members; third floor, club rooms for both ladies and gentlemen; and fourth floor, lodge and banquet quarters. The roof garden was still an undecided option, “but so many members favor having a private retreat next to the stars where they may commune with nature or each other in the cool summer breezes, that this feature is practically assured, also.” Finally, it noted that with a budget limited to $75,000 the building could only be partially fireproof.

(It is not known whether Henry Osterman, the most prolific architect in Walla Walla at the time and a member of Lodge 287, submitted a proposal for the new Elks’ Temple. His name was prominent on one of the tiles that comprised the facing of the fireplace at the entrance to the Club Room.)

Up-To-The-Times reported extensively on local Elks activities in its March 1912 issue, as follows: “Walla Walla Elks have already chartered a special train to take them to the Elks’ National Convention which is to be held in Portland in July. The local members of the lodge will wear novel suits, made of sack jute from the penitentiary, which will be dyed purple. White hats will complete the regalia. Eight Pullman coaches have already been reserved and it is believed even more will be taken before the convention time arrives.” One can easily conclude that the local Elks were hyped to promote their anticipated grand new building at the national convention.

More specific to the building itself, the article went on to report, “A $75,000 club house will be built this summer by the Elks of Walla Walla. The plans adopted call for a four-story structure of red brick, faced with cream colored brick, the first floor for store purposes, the second for dormitory rooms, the third for club rooms and the fourth for lodge rooms. A roof garden is also proposed.”

The Elks building committee selected the proposal from Linde & Ulrich of Portland. In its April 1912 issue, Up-To-The-Times featured a three-quarter view line drawing of the proposed building, signed by Carl L. Linde, that depicts a four-story temple. The structure as completed was five stories; thus Linde’s line drawing probably was part of his initial proposal that called for a four- or five-story structure. The Pacific Coast Architect magazine in April 1912 noted, “Architect Carl Linde is preparing plans for a five-story pressed brick Elks’ temple to be erected in Walla Walla, Wash., at a cost of $100,000.” This suggests that the decision to build a five-story building at an additional cost of around $25,000 was made most likely in March.

Despite the fact that it appears a decision tentatively had been reached six months earlier to construct a five-story building, on August 1, 1912 Building Permit 1341 was issued to the B.P.O.E. for a four-story brick building at Fourth and Alder, estimated to cost $55,000. J. A. McLean, a noted local builder whose imposing residence is extant at 1049 Alvarado Terrace, was the designated contractor.

By November 1912, Up-To-The-Times was able to report, “The Elks’ new temple, Walla Walla, is rapidly nearing completion. The building, when completed, will cost $105,000. It will be ready for occupancy on first of February, 1913.” The following month the magazine wrote, “Two elevators will be installed in the new Elks’ temple, Fourth and Alder streets.” In January 1913 it noted, “The Elks’ new temple, Walla Walla, one of the finest buildings of its kind in the state of Washington, is to be opened with appropriate ceremonies some time next month.”

Continuing its monthly coverage, Up-To-The-Times reported more extensively in February 1913, “The building committee of the new Elks’ Temple, Walla Walla, has completed arrangements for the installation of a huge bronze elk, one and one-half times life size, which will be placed upon a 30-foot pedestal on top of the temple. [The pedestal was directly above the two elevators; thus, its primary function was to provide housing for the elevator machinery, with secondary function as a mount for the bronze elk.] It will be brilliantly illuminated at night with small incandescents.” However, as construction fell behind schedule, the magazine limited its coverage to a line or two in March and April, noting in May 1913, “The Walla Walla Elks have postponed the dedication of their new temple from May 6, 7 and 8 to May 22, 23 and 24.”

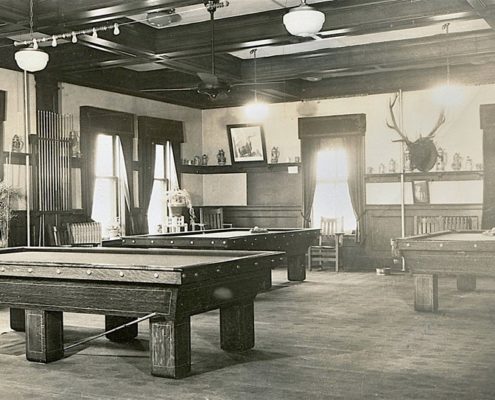

Finally, on May 24, 1913, the Walla Walla Union was able to report in rapturous prose that the new Elks’ Temple, the final cost for which had reached $125,000, was “five stories with a wooden pergola around the roof’s edges for clinging vines and potted plants, to enclose the city’s first roof garden… On the topmost point of the building commanding the city, in alert position, stands a massive bronze statue, clearly in relief on the horizon by day, electric lighted by night; ever a friendly beacon testifying that a heaven lies beneath… The first floor contains seven small sized [commercial retail] store rooms, neatly finished inside, with storage room in the rear… two elevators are immediately to the right of the entrance. These elevators are something new and unique in Walla Walla in that they are self started and stopped and no attendant boy is needed. They are operated entirely by push buttons inside and out.” The newspaper’s account goes on to describe the second floor as having 16 furnished rooms, all but two with private baths, with a common bath for the other rooms, and all heated by a steam plant in the basement. The building was piped for an automatic vacuum cleaning plant, although this was not yet operational at the grand opening. The third floor contained the Club Room with a spacious lobby at the head of the stairs “with massive columns” and a ceiling of “large Colonial beams and calcimated plaster.” The front section of the Club Room was a Reading Room with a “historic fireplace made of 300 purple-gray enamel bricks, upon each of which is carved the name of a lodge member. [The account of the fireplace tiles did not mention that each man whose name appeared on a tile had made a donation to the construction of the building. These tiles were salvaged when the building was razed in 1973 and are mounted on walls of the entrance hall to the current lodge at 351 East Rose Street.] At the rear was the Billiards Room with one pool and two billiard tables. Windows were hung with purple draperies. The fourth floor contained the Lodge Room, 70 by 43 feet and two stories in height with an ornamental plaster ceiling and purple draperies. This level also contained a ladies parlor finished in mahogany and Spanish leather. That portion of the fifth floor not taken up by the two-story lodge room contained a Banquet Room, a kitchen separated from the Banquet Room to preclude “any offensive odors,” and a dumb waiter for sending up supplies. Finally, the roof garden was described as being 60 by 110 feet, with “wooden flooring… and the pergola surrounding is already being fitted up with plants and vines… An orchestra box will be arranged… A fine view of the valley can be obtained from this vantage point.” The purple prose contained in this news account was befitting the occasion, the official Elks colors being purple and white. Indeed, for the grand opening of the new lodge, Pacific Power & Light changed the cluster of street light globes around the building to purple.

The Walla Walla Union reported on May 25, 1913 that 1,000 visiting Elks arrived in Walla Walla for the three-day dedication ceremony, representing different lodges from Portland, Maine to Berkeley, California.

The following month, Up-To-The-Times in June reflected on the grand opening as follows, “The finest lodge home in the entire Northwest was dedicated last month when the Local Lodge No. 287 of the B.P.O.E. of Walla Walla formally opened the doors of its magnificent new four-story [sic] building. The services extended over three days, May 22, 23 and 24, and were attended by hundreds of Elks from all parts of the Northwest, many coming in special cars chartered for the occasion. The formal dedication occurred on Friday, and public receptions, lodge work and parades were included in the list of events…”

The completed Elks’ Temple was indeed a striking building. Its design projected a restrained Beaux Arts appearance. Facing of the building was of cream colored brick; quoins at the corners of the building were of the same material, perhaps a cost-saving concession to more expensive sandstone or imported Indiana limestone. The entrance to the Elks’ portion of the building was at the far right of the east façade, classic in form, but certainly not imposing, its main feature being two rather squat Doric columns supporting an entablature that tended to impart a rather Lilliputian look to the entrance of this otherwise imposing building. The balance of the ground level spaces facing both Fourth and Alder were reserved for commercial tenants. A string course stretched the length of both street façades above the first floor. The main cornice, were it not for its size and location above the fourth floor rather than the fifth or top floor, would be described as a cavetto cornice. It was a heavy, albeit simple, cornice save for the four pediments at the corners of the two street façades with ornate supporting brackets. The façade of the fifth floor that extended above this cornice was simpler than the lower floors, lacking windows on both street façades. At roof level were numerous substantial poles supporting the pergola – that actually was more of a trellis than a pergola. Wrought iron balconies, from appearances probably ornamental, embellished six window groupings on the third and fourth floors.

Part 2: The In-Between Years

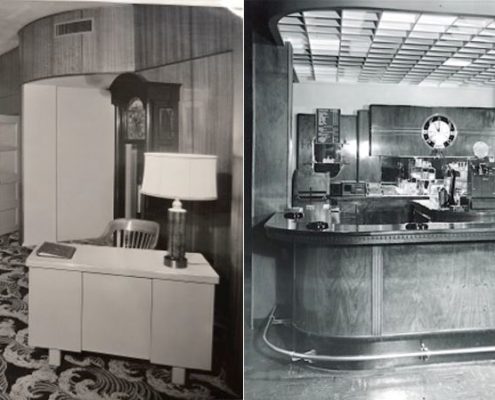

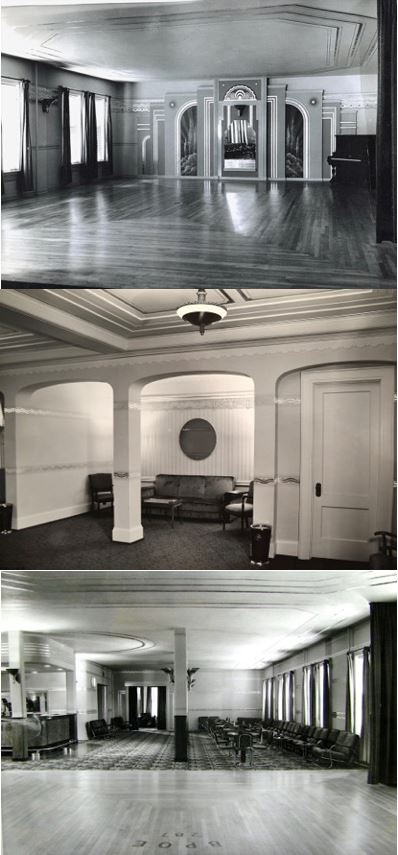

A trio of photos depicting the 1938-39 remodel, displaying Streamline Moderne with touches of Hollywood Regency. Left top and bottom are two views of what probably had been the fifth floor Banquet Room. Top right is what perhaps might be a ladies lounge, presumably also on the fifth floor. All courtesy Joe Drazan.

Although a number of photographs exist of various events at the Elks’ Lodge over the years until a fire that destroyed a good portion of the building in 1970, many of these are not identified as to time or place. Archived documentation has been difficult to locate; most material in the basement archives of the current lodge building on Rose Street does not predate the move into that building in 1973. Undoubtedly, considerable historical data was lost to the fire in 1970.

The mortgage on the Elks’ Temple was paid off April 1, 1938. That having been accomplished, some of the interior spaces of the old temple were remodeled in 1938-39. Where some of these spaces were located in the building has been difficult to determine. Additional interior remodeling was completed in 1953. Retired Walla Walla attorney and deputy prosecuting attorney, Albert “Red” Golden, who became a member of Elks’ Lodge 287 in the 1950s, provided valued assistance in establishing locations of a number of rooms in the building.

The grand Lodge Room on the fourth floor appears to have remained intact as completed in 1913. Photos of rooms and areas that were remodeled in 1938-39 display stylish Streamline Moderne with touches of Hollywood Regency for which it was apparent no expenses were spared for light fixtures, furnishings and other accoutrements. Arguably the most imposing space that resulted from the 1938-39 remodel was a large dance and reception area with a bar to one side. The dance floor was hardwood with BPOE 287 either inlaid or painted on the flooring. It is assumed that this space was located on the fifth floor in the former Banquet Room; post-fire photos confirm it was destroyed in the 1970 fire that was largely limited to the fourth and fifth floors.

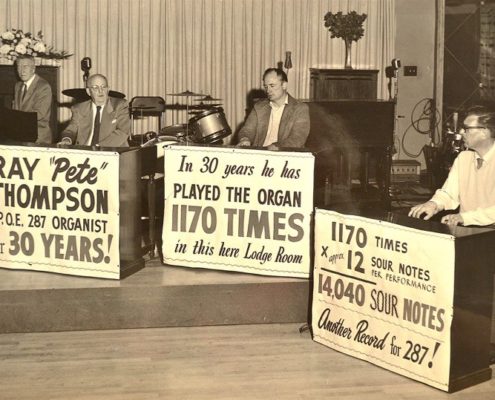

While it was not uncommon for Elks temples to have a pipe organ in the Lodge Room, a pipe organ was not installed in the Walla Walla Lodge Room. However, there were organists at this lodge who probably skittered across the ivories on the likes of such imitative devices as a Hammond B-3. The Union-Bulletin reported on March 20, 1958, “G. Ray ‘Pete’ Thompson… received recognition for his 30 years as organist of the Walla Walla Elks’ Lodge at this week’s meeting. At the consoles of electric organs behind the signs are: left to right, Hayden Mann, Bill Hauber and Dawson Funk. A bit of good-natured ribbing also was involved, as noted on the sign at right.”

On March 31, 1960, the Union Bulletin wrote, “More than 100 boys and their fathers attended the second in a series of father and son banquets at the Elks’ Temple Wednesday night. Before and after the chicken dinner the boys and their fathers listened to organ music by Dawson Funk, lodge organist.” (Dawson Funk owned a Volkswagen dealership at Wellington and Walla Walla Avenues. In a photo ad from 1955 he is shown with Mrs. Funk, both holding a variety of elk antlers with a profusion of antlers on the floor surrounding the VW convertible featured in the photo. Their son, who appears to be about eight years old, is sitting at the wheel with more elk antlers filling the car’s back seat.)

By the mid-1940s, the wooden trellis around the perimeter of the cornice had disappeared; whether the roof garden remained beyond that point is unknown. A photo of the Elks’ Temple dated 1949 reveals several unsightly exterior fire escapes cluttering the façades of the building, and the original Doric columns at the entrance had been discarded, replaced by curved walls of glass blocks, unbefitting the building’s classic architecture.

A search of deeds at Pioneer/Columbia Title revealed a lease filed May 14, 1942 from the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks to the State of Washington for 2,340 square feet on the ground floor, encompassing former storefronts 208, 210 and 212 West Alder Street. The lease was for twelve months, April 1, 1947 through March 31, 1948 at $200 per month.

In the 1960s, ballroom dancing lessons were given to local high school students. Classes were held in the grand Lodge Room on the fourth floor. Parke Thomas of Walla Walla, whose father was pastor of First Congregational Church at the time, recalled, “Our teachers were a couple and I don’t remember the man too well, but she was quite pretty, wore skirts that swirled and suggested chiffon, and, as I recall, quite high heels. Her hair, if I remember it correctly, was always carefully arranged and was not of a style likely to blow freely in a breeze. I remember they both smiled a great deal and even in that time period taught us to bow when asking a girl to trip the light fantastic. I believe we boys all had to wear sport coats or suits in order to participate.”

Parke also reflected on, “the fun of going to the Elks Club for Thursday dinner, which we did quite often. It involved riding up in a magical and barely functional lift which opened into a dining room that to me seemed right off the Queen Mary. Drapes and mirrors and a couple of levels. Lots of room for mentally transporting oneself to more glamorous environs and times!”

Additional interior remodeling undertaken in 1953 did not display the expense or commensurate attention to detail of the 1938-39 alterations. It is interesting to see that the tall, beautiful grandfather clock that appears in the entry hall to the original third floor Club Room, and that continues to grace the entry hall of the current lodge building on Rose Street, incongruously conspicuous in a photo of the remodeled club entrance off Fourth. To the left of the entrance and front desk was a waiting room where wives could relax while their husbands repaired to the Stag Room and bar behind the entrance and front desk, with a card room at the southwest corner of the first floor. (The Stag Room had a key card entrance directly from the parking lot behind the Hotel Dacres for members who arrived “stag.”)

Whether any of the apartments on the second floor were remodeled is unclear, but they continued to occupy that floor until the demise of the building.

Most walls in existing photos of the third floor Dining Room show a profusion of mahogany paneling – large solid sheets rather than vertically-grooved Weldwood paneling ubiquitous in homes at the time – lowered ceilings, indirect lighting, and quilted leather surrounds enclosing large mirrors, all consequences of the 1953 remodel. There were also a kitchen and office on this floor.

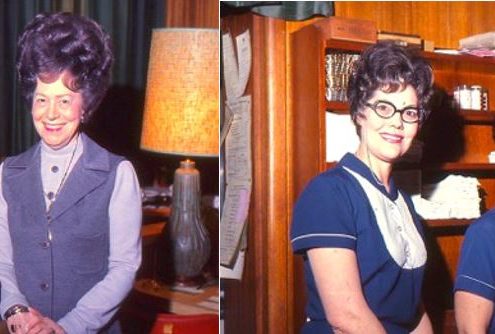

Shortly before the building was torn down in April 1973, a number of photos were taken of the Dining Room, including the bar and stage with musicians’ instruments, long tables of buffet food and staff, including a bartender and Dining Room waitresses.

The most riveting photo from this collection is of a woman who appears to have probably been in her sixties at the time, and judging from her mien was most likely the hostess in the Dining Room. The most compelling thing about her was her hair style, a twelve-inch tall pile of curls dyed a lustrous shade of purple. As if that weren’t striking enough, she was dressed in purple and pink. Surely there was a story here that needed to be found. Eventually, information filtered in that this woman was indeed the hostess, married to a man whom the source of this information could only remember by the name of “Booty” Irving, who was described as having handled all of the Elks’ financial matters. Further investigation disclosed that Percy “Booty” Irving, a lifelong Walla Walla resident, was remembered at his memorial service as “the man who ran the Elks Club” for nearly 30 years. His second wife, Deloris, was the purple-bewigged Elks hostess.

Part 3: The Fire and Final Years

A Union-Bulletin photo from May 23, 1970 shows smoke still exiting windows of the fourth and fifth floors. Elks’ Lodge photo, courtesy Joe Drazan.

Friday night, May 22, 1970 a passerby entered the Elks’ Temple to notify staff that smoke was pouring from an upper floor window. A fire had broken out on the fourth floor and by the time it was brought under control hours later much of the fourth and fifth floors was largely destroyed. A cigarette dropped into a davenport in a corner room of the fourth floor – the ladies parlor, perhaps – was determined to be the cause of the fire. An open staircase from the fourth to the fifth floor quickly carried the flames upward. It did not take long for to the fire burn through the fifth floor ceiling and into the attic, coming close to burning through the roof. Somehow, the two-story grand Lodge Room on the fourth floor reportedly was mostly spared from destruction.

Unaware of the fire above them, patrons in the Dining Room on the third floor continued to enjoy their Friday night buffet dinners. The first notice to evacuate, delivered over the public address system, went unnoticed. It was repeated, “There’s a fire in the building, everybody will have to leave.” An orderly evacuation was completed in five minutes’ time, some members taking their buffet plates downstairs with them. Two staff members assisted helping elderly Elks members who lived on the second floor leave the building.

As the fire was in its early stage, many off-duty Walla Walla firemen were supervising an evening performance of a circus the fire department was sponsoring at Borleske Stadium. Spotting the smoke, the firemen notified their wives to come to Borleske Stadium to oversee the evening’s events there, while they rushed to the Elks’ Temple to fight the fire.

How long it took to control the fire is not known, but photographs taken on Saturday morning and published in the Union-Bulletin on Sunday, May 24th show smoke continuing to exit windows. The fourth and fifth floors were unusable. While it was reported that the Lodge Room was spared, it surely must have suffered significant water damage and falling plaster. Albert Golden recalled that the Lodge Room was used for meetings for a time, but that eventually board meetings were held in the ladies waiting room on the first floor. Apparently damage to the first three floors of the building was limited to water and smoke damage. The Elks were able to return these floors to use once cleanup and repairs had been made.

At the time of the fire the Elks’ Temple had just passed the 57th year since its dedication. Although it continued to function on a certain level, if not exactly old, it was damaged and tired. It was also a large building, its facilities and equipment outdated and inadequate.

Presumably, by 1971 or 72 a decision was reached to sell the old building and construct a modern one-story new lodge on the block bounded by East Rose and Sumach, North Palouse and Tukanon Streets. The Elks began negotiating with Walla Walla County Commissioners and the Downtown Development Association for the purchase of the old lodge building, preparatory to their move to their new building on Rose Street, tentatively scheduled for May 1973 – 60 years to the month after their move into the old temple.

The firm of A. Ritchie Company was hired to remove the bronze elk from its rooftop perch, to be installed on the roof of the new lodge. On February 22, 1973, the elk’s antlers were removed in order to lower it through the roof of the elevator housing on which it had stood for 60 years to the main roof. The only damage the old bull elk suffered was the loss of one ear in the elevator shaft. The remainder of its descent to street level was accomplished without incident on scaffolding set up on the side of the building. (The bronze elk has been stolen twice from its roof perch at the current lodge. Although retrieved following both thefts, it did suffer damage each time. Thus, a decision was made to display it permanently inside the front entrance to the building.)

Left, the Elks’ drum corps in an early photo of the entrance to the Elks’ Temple. Courtesy Elks’ Lodge 287. Right, the entrance in a final photo from July 1973, showing fallen rubble from upper floors. Courtesy Elks’ Lodge 287.

Finally, the new lodge completed and the old temple vacated, on July 19, 1973 a wrecking ball began knocking down the walls. The Union-Bulletin reported the following day, “The sight of the huge ball hammering its lofty walls to bits was enough to jolt the sentiments of members who for decades had passed through its now-tottering portals in pursuit of relaxation, conviviality and fraternal endeavors… the old structure has been waiting to give up the ghost in favor of the modern lodge building concept and for restructuring of the downtown area.”

In mourning the loss of yet another slice of historic downtown Walla Walla, one must consider the facts: it was a five-story building that had been heavily damaged by fire, rendering the cost of restoration, if even possible, most likely beyond the financial resources of the local lodge. As the late Seattle boat builder, Norm Blanchard, observed about a once-beautiful motor yacht, lying derelict, that his father had built in 1919, “Sometimes it’s best to just let them slip away.”

Carl L. Linde

Architect Carl L. Linde was born in Brunswick, Germany on May 21, 1864. He emigrated with his parents to the United States in 1870, the family settling in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. There he attended Milwaukee’s German-English Academy and apprenticed to an architect. In 1883, he traveled to New York where it is reported that he worked as a draftsman for the distinguished firm of McKim, Meade & White; this has not been established for certain, although his early architectural work was strongly derivative and traditional, as one might expect of a young aspiring architect working for that firm.

Leaving New York, Linde returned to Milwaukee, later moving to Chicago where he worked on several high-rise buildings between 1888 and 1892 before returning to Milwaukee. He married Hattie Lebus of Milwaukee in 1890. They moved west to Portland in 1906 where Linde worked as an architect until 1940. It is unknown how long his partnership with Ulrich existed, but the firm’s entire involvement with the Walla Walla Elks project appears to have been limited to Linde.

Linde designed numerous apartment buildings and residences in Portland. A number of his buildings are on the National Register of Historic Places. For a time he maintained a second office in Seattle, where he designed the Camlin Hotel and Puget Sound Savings & Loan. Linde was a member of the Oregon Chapter, American Institute of Architects, and served as vice president in 1934. He died in Portland July 12, 1945.

References

- Whitman Archives

- Sanborn Fire Map, 1905

- Up-To-The-Times, various dates

- Pioneer Title/Columbia Title

- The Morning Union, various dates

- Walla Walla Union, various dates

- Walla Walla Union-Bulletin, various dates 1970s

- Diana Bieker, Leading Knight, Walla Walla Elks Lodge 287

- Hawkins, William J, III and William F. Willingham, Classic Houses of Portland, Oregon 1850-1950, Timber Press, Portland, 1999

- The Pacific Coast Architect, April 1912

- Joe Drazan, Bygone Walla Walla blog

- Ritz, Richard Ellison, Architects of Oregon: A Biographical Dictionary of Architect Deceased, 19th and 20th Centuries, Lair Hill Publishing, Portland, 2003

- United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Nationa Register of Historic Places

- Lyman, Prof. W. D., History of Old Walla Walla County Embracing Walla Walla Columbia, Garfield and Asotin Counties, Vol. 1, S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, Chicago, 1918

- Albert “Red” Golden, Lodge 287 member since 1950s

- Parke Thomas